Paul R Salmon FCILT, FSCM, FCMI

When Better Models Deliver Worse Outcomes in Modern Supply Chains

Introduction: The Optimisation Paradox

Few ideas in supply chain management are as widely embraced as optimisation. For decades, organisations have invested heavily in tools and techniques designed to reduce cost, compress inventory, improve service levels, and extract maximum efficiency from complex networks. Optimisation models sit at the heart of planning systems, network design, inventory policy, transport routing, and production scheduling.

Yet despite increasingly sophisticated analytics, many supply chains remain fragile, slow to respond, and prone to cascading failure. In some cases, they perform worse after optimisation than before.

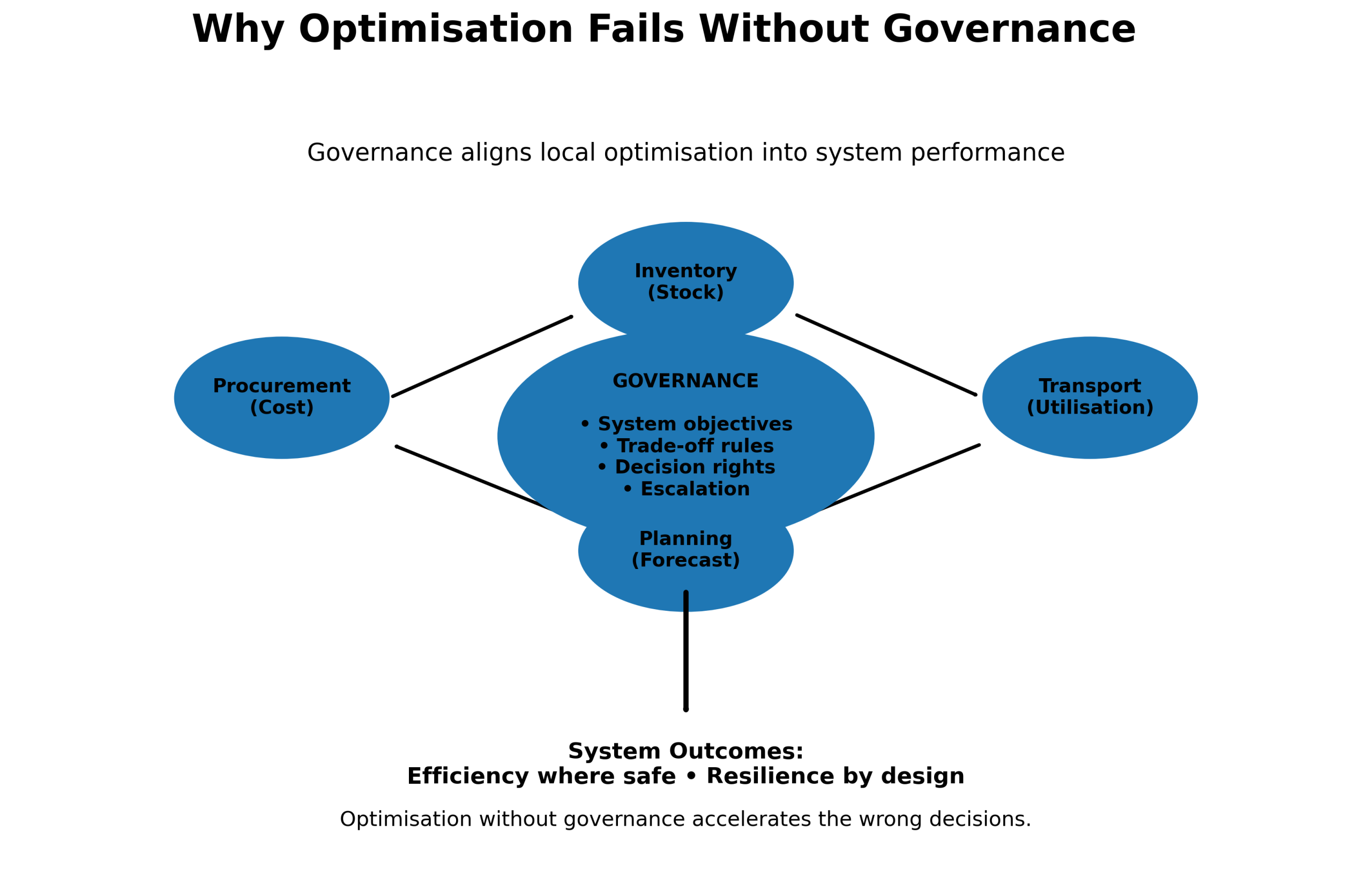

This apparent contradiction reflects a fundamental truth: optimisation does not fail because the mathematics are wrong; it fails because governance is missing. Without clear decision rights, accountability, and system-level oversight, optimisation simply accelerates local decisions that undermine overall performance.

As supply chains move into an era defined by uncertainty, contested resources, and strategic dependency, optimisation divorced from governance is no longer merely ineffective — it is actively dangerous.

What Optimisation Is — and What It Is Not

At its core, optimisation is the disciplined pursuit of an objective subject to constraints. Whether the objective is cost minimisation, service maximisation, or throughput stabilisation, optimisation requires clarity about three things:

what success looks like, what trade-offs are permitted, and which constraints are inviolable.

The problem is that in many organisations, these elements are either poorly defined or inconsistently applied. Optimisation is often treated as a technical exercise, delegated to analysts and planners, while the harder questions of who decides, on what basis, and in whose interest remain unresolved.

Optimisation is not strategy. It does not determine what should be optimised, for whom, or over what time horizon. Those questions are matters of governance. When governance is absent, optimisation fills the vacuum — not with wisdom, but with unintended consequences.

Local Optimisation: The Most Common Failure Mode

The most pervasive optimisation failure is local optimisation. Functions, contracts, and organisations optimise their own objectives in isolation, assuming that system-level performance will improve as a result. In reality, the opposite is often true.

Procurement optimises unit cost by concentrating spend, increasing supplier dependency. Inventory teams optimise working capital by reducing buffers, eroding resilience. Transport teams optimise utilisation, increasing lead-time variability. Commercial teams optimise contractual risk transfer, obscuring operational accountability.

Each decision may be rational within its local frame. Collectively, they degrade the system.

Without governance to arbitrate trade-offs, optimisation becomes a competition rather than a coordination mechanism. The result is a supply chain that is efficient in fragments and ineffective as a whole.

The Myth of the Objective Function

Optimisation models rely on objective functions — mathematical representations of what the organisation values. In practice, these functions are often proxies rather than truths.

Cost is used as a surrogate for value. Service level targets are treated as absolutes rather than negotiated outcomes. Risk is approximated or ignored altogether. Long-term consequences are discounted in favour of short-term gains.

The deeper issue is not technical limitation, but organisational ambiguity. When leadership has not explicitly prioritised objectives or defined acceptable trade-offs, optimisation models embed assumptions by default. Those assumptions then acquire unwarranted authority because they are expressed numerically.

Governance is the mechanism by which objective functions are legitimised, challenged, and revised. Without it, optimisation models optimise the wrong thing very efficiently.

Optimisation Without Decision Rights

One of the least discussed aspects of optimisation failure is decision rights. Optimisation outputs are often presented as recommendations without clarity about who is authorised to act on them.

Is a planner allowed to reallocate stock across regions? Can a commercial team override a network design recommendation? Who decides when resilience should trump cost? When these questions are unanswered, optimisation results are either ignored or applied inconsistently.

Worse still, decisions are sometimes made implicitly through system parameters rather than explicitly through governance forums. Safety stock levels, lead-time assumptions, and penalty weights encode decisions that no one remembers agreeing to.

In such environments, optimisation does not inform decisions — it obscures them.

The Contractual Blind Spot

Optimisation frequently fails at organisational boundaries. Contracts, not models, determine behaviour across supply chains. Yet optimisation is often performed as if contractual structures are neutral.

In reality, contracts embed incentives, penalties, and risk allocations that shape decisions far more powerfully than analytical insight. A transport contract that rewards utilisation will undermine an optimisation that values responsiveness. An availability contract without shared data will resist system-level optimisation. A fixed-price support arrangement may discourage adaptive behaviour altogether.

When governance does not align contracts with optimisation intent, models generate theoretically optimal solutions that are practically unattainable. The result is frustration, not performance improvement.

The Absence of System Authority

Complex supply chains are federated systems. They span functions, organisations, and sometimes nations. In such systems, optimisation requires a recognised authority capable of making decisions that transcend local interests.

Too often, no such authority exists. Governance bodies are advisory rather than directive. Decisions are deferred to consensus, which is slow and risk-averse. Optimisation outputs circulate without ownership.

In the absence of system authority, optimisation becomes a technical exercise disconnected from power. The models may be correct, but they lack the mandate to change behaviour.

Effective governance does not require centralised control over every decision. It requires clarity about which decisions are local, which are system-level, and who has the right to decide in each case.

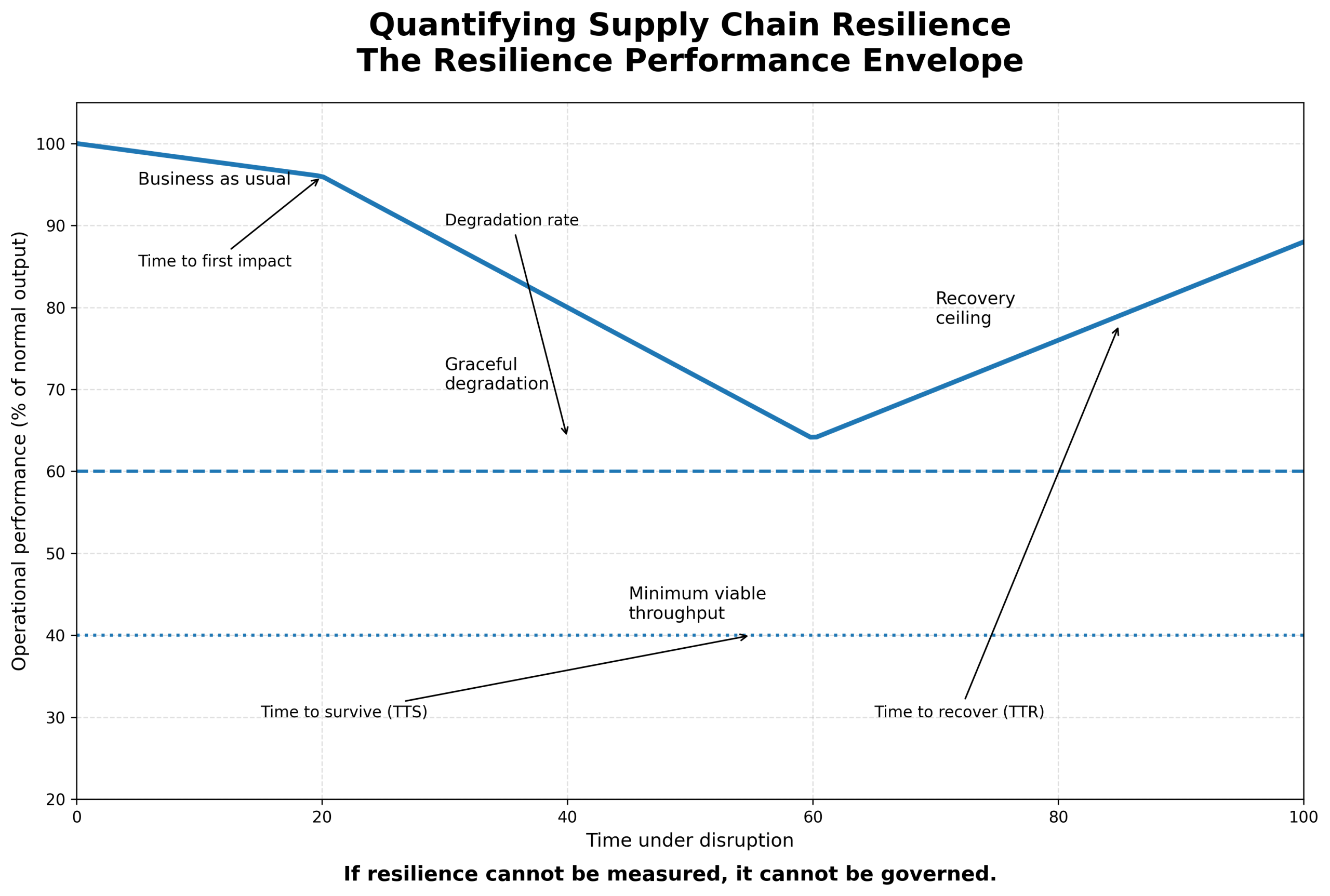

When Optimisation Increases Fragility

Perhaps the most counterintuitive failure mode is when optimisation actively reduces resilience. Lean inventory, single sourcing, just-in-time logistics, and tightly coupled networks all emerge from legitimate optimisation objectives. Yet they also increase sensitivity to disruption.

This is not an argument against efficiency. It is an argument against efficiency pursued without guardrails. Governance provides those guardrails by defining minimum survivability thresholds, acceptable dependency levels, and conditions under which efficiency must be sacrificed for endurance.

Without governance, optimisation optimises away slack — and slack is often the very thing that absorbs shock.

The Governance Gap in Digital Supply Chains

As supply chains digitise, the governance challenge intensifies. Advanced planning systems, digital twins, and autonomous optimisation engines increase speed and scale. Decisions that once took weeks now occur in minutes.

This amplifies both benefit and risk. Poorly governed optimisation can propagate errors faster than humans can intervene. Parameter changes can have system-wide effects that are poorly understood.

Digital optimisation demands stronger governance, not weaker. Decision logic must be transparent. Overrides must be defined. Accountability must be explicit. Otherwise, automation simply accelerates dysfunction.

What Good Governance Looks Like

Governance does not mean bureaucracy. It means structure, clarity, and intent. In well-governed supply chains, optimisation is embedded within a decision framework rather than operating in isolation.

Key characteristics include:

clearly articulated system-level objectives, explicit prioritisation of cost, service, resilience, and sustainability, defined decision rights across organisational boundaries, agreed escalation thresholds and trade-off rules, and alignment between contracts, incentives, and optimisation goals.

In such environments, optimisation models become decision support tools rather than de facto decision-makers.

From Optimisation to Stewardship

The most resilient supply chains are governed as systems, not collections of functions. Leaders act as stewards rather than optimisers, recognising that long-term performance depends on coherence as much as efficiency.

Stewardship reframes optimisation as a means rather than an end. It asks not only what is optimal now, but what remains viable under stress. It values optionality alongside efficiency and transparency alongside precision.

This shift is cultural as much as structural. It requires leaders to engage with trade-offs openly rather than hiding behind models.

Why This Matters Now

The operating environment facing supply chains in 2026 and beyond will be defined by volatility rather than equilibrium. Energy constraints, geopolitical friction, labour scarcity, and climate impacts will challenge assumptions embedded in decades of optimisation thinking.

In this context, governance is not a constraint on optimisation. It is the condition that makes optimisation safe.

Supply chains that continue to optimise without governance will become faster, cheaper, and more brittle. Those that embed optimisation within strong governance will be adaptable, credible, and trusted.

Conclusion: Optimisation Needs Authority

Optimisation is powerful. It can reveal insight, expose inefficiency, and improve performance. But without governance, it cannot deliver what leaders expect of it.

The question facing supply chain leaders is not whether to optimise, but how optimisation is governed. Who decides what matters? Who arbitrates trade-offs? Who owns system outcomes?

Until those questions are answered, optimisation will continue to fail — not because it is wrong, but because it is ungoverned.

In the decade ahead, the most successful supply chains will not be those with the most advanced models, but those with the clearest authority to use them wisely.

Optimisation without governance is not optimisation at all. It is abdication.

Leave a Reply