Paul R Salmon FCILT, FSCM, FCMI

From Narrative Comfort to Quantified Readiness in Modern Supply Chains

Introduction: Why Resilience Now Demands Proof

Few words are used more frequently in modern supply-chain discourse than resilience. Boards demand it. Governments fund it. Annual reports celebrate it. Yet for all its popularity, resilience remains one of the least precisely defined and least consistently measured attributes of supply-chain performance.

Most organisations can articulate why resilience matters. Far fewer can explain what it actually means in operational terms. Fewer still can evidence it quantitatively.

This matters because resilience has moved from a desirable characteristic to a strategic obligation. Supply chains underpin national infrastructure, public services, defence capability, and economic stability. As disruptions become more frequent, more complex, and more systemic, reassurance and narrative confidence are no longer sufficient. Decision-makers are increasingly asking not whether a supply chain is resilient, but how resilient it is — and at what cost.

The central argument of this article is straightforward: if resilience cannot be expressed in numbers, it cannot be governed; and if it cannot be governed, it cannot be relied upon. To set the tone for 2026 and beyond, resilience must transition from rhetoric to evidence, from aspiration to decision-grade measurement.

The Resilience Illusion

Many supply chains describe themselves as resilient because they survived a recent disruption. A pandemic was endured. A supplier failure was managed. A geopolitical shock was absorbed. Survival, however, is not the same as preparedness.

This retrospective logic creates what might be called the resilience illusion: the belief that because a system recovered once, it will recover again under different, potentially more severe conditions. In practice, many organisations mistake fortune for capability.

The illusion is reinforced by familiar artefacts. Risk registers use colour-coded heatmaps that lack thresholds or tolerances. Scenario exercises generate discussion but no measurable outputs. Supplier assurance processes confirm compliance but not dependency or substitutability. These tools offer comfort, not control.

True resilience is not a label applied after the event. It is a demonstrable capability to sustain performance under defined stress. Without quantified boundaries, resilience remains an opinion rather than a property.

Resilience as a Performance Envelope

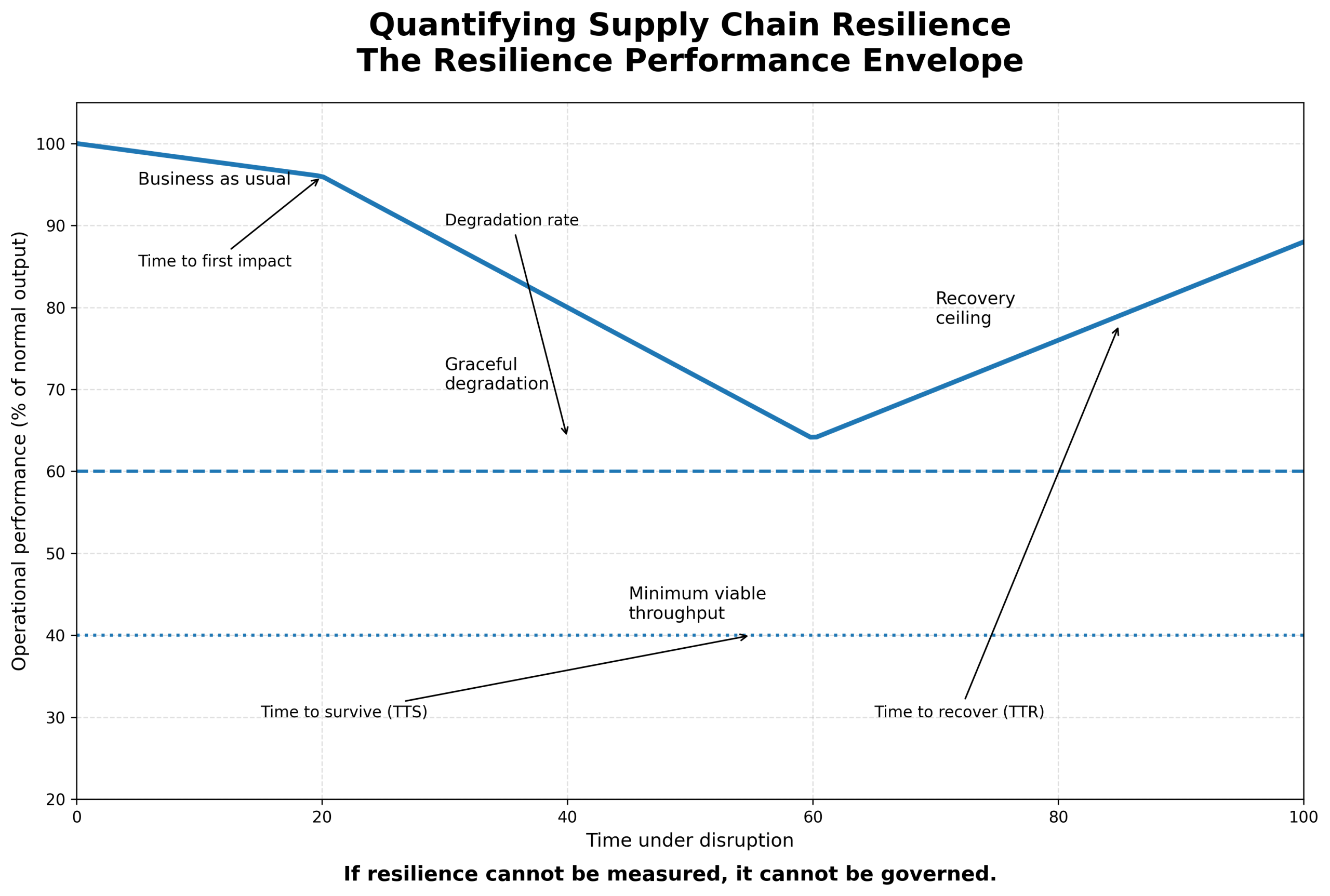

A more useful way to think about resilience is as a performance envelope rather than a binary state. A resilient supply chain is not one that never degrades, but one that degrades in predictable, manageable ways and within agreed limits.

This reframing shifts the question from “Are we resilient?” to “How does our performance behave under stress?”

A performance envelope defines:

the level of output that can be sustained, under specific disruption conditions, for a defined duration, with an understood consumption of resources.

The difference is significant. Saying “our supply chain is resilient” offers little insight. Saying “we can sustain 70 per cent output for 90 days with a 30 per cent logistics constraint” provides a basis for decision-making. Precision of language is the first step towards precision of measurement.

Five Questions That Define Quantified Resilience

To move from narrative to numbers, every resilient supply chain must be able to answer five fundamental questions. Together, they form the backbone of quantified readiness.

First: resilient to what?

Resilience is always relative to a stressor. Demand volatility, supplier insolvency, energy shortages, cyber disruption, infrastructure denial, and workforce constraints each stress supply chains in different ways. A supply chain resilient to demand shock may be fragile under energy constraint. Without specifying the disruption, resilience claims are meaningless.

Second: how fast does performance degrade?

Disruption rarely causes instant collapse. Performance usually declines over time. Measuring the rate of degradation — the slope of decline rather than the endpoint — reveals how much decision time exists and how rapidly interventions must occur.

Third: how far can performance fall and still function?

Most supply chains have a minimum viable throughput below which the system ceases to deliver meaningful value. Identifying this threshold clarifies which services are essential and which can be deferred under stress.

Fourth: how long can degraded operation be sustained?

Time-to-survive matters as much as time-to-recover. Stock buffers, cash flow, workforce endurance, and contractual flexibility all determine how long a supply chain can operate below normal conditions before irreversible damage occurs.

Fifth: how quickly and how fully can performance be restored?

Recovery is not always a return to the original state. Measuring time-to-recover and the achievable post-recovery performance level prevents unrealistic assumptions about rebound and highlights long-term scarring effects.

If an organisation cannot answer all five questions quantitatively, it is not managing resilience. It is hoping for it.

From Heatmaps to Hard Metrics

The challenge is not a lack of data, but a lack of structure. Resilience measurement requires a layered approach that moves from structure to dynamics to decisions.

At the structural level, metrics describe the shape of the supply chain. These include dependency concentration ratios, single-point-of-failure counts, geographic clustering, energy intensity per unit output, and reliance on constrained skills or materials. Structural metrics reveal where fragility is embedded by design.

At the dynamic level, metrics describe behaviour under stress. Time-to-survive, time-to-recover, degradation rates, recovery slopes, and buffer consumption profiles show how the system responds when disrupted. These metrics transform resilience from a static property into a time-based capability.

At the decision level, metrics force trade-offs. What does each additional percentage point of survivability cost? How much redundancy is required to halve recovery time? What is the opportunity cost of resilience investments relative to efficiency gains? These questions elevate resilience from risk management to strategic choice.

Crucially, good metrics do not simply describe risk. They compel leadership decisions by making consequences visible.

Why Quantification Is So Often Avoided

Despite its importance, quantified resilience remains rare. This is not due to technical difficulty alone. More often, it is avoided because numbers are uncomfortable.

Quantification exposes hidden dependencies, underinvestment, and optimistic assumptions. It reveals that resilience has a price and that not all risks can be mitigated simultaneously. It challenges narratives that have gone untested.

There is also a cultural dimension. Many organisations prefer flexibility over commitment, optionality over thresholds. Quantified resilience introduces explicit tolerances and agreed limits. Once these exist, deviations demand explanation.

Narrative resilience is convenient. Quantified resilience is accountable.

From Measurement to Governance

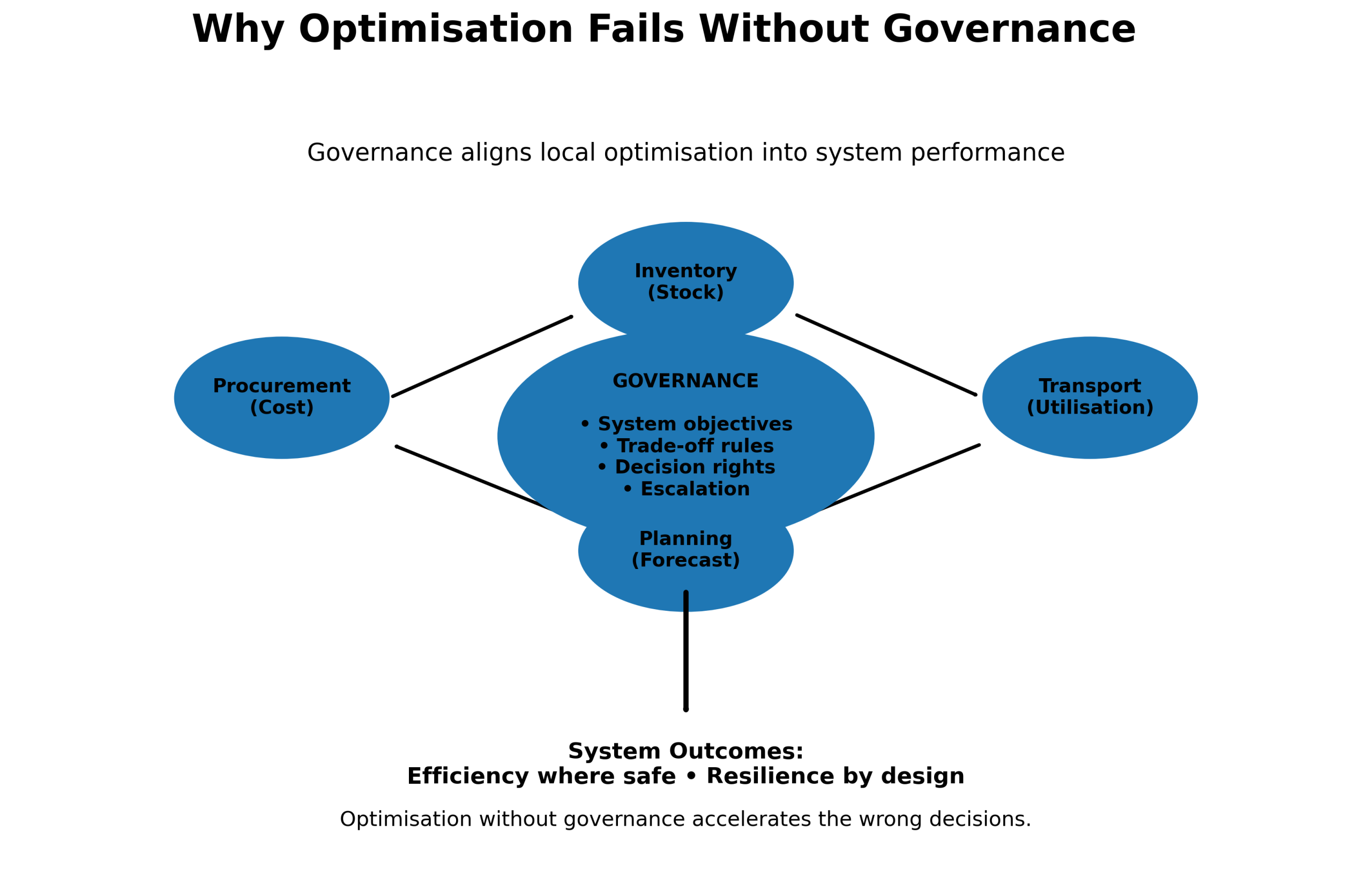

Measurement without governance is analysis without impact. For resilience to influence outcomes, metrics must be embedded into decision structures.

This begins at board level. Resilience metrics should sit alongside financial, safety, and regulatory indicators. They should inform investment decisions, contract design, and strategic priorities. Importantly, they should trigger pre-authorised actions when thresholds are breached, rather than ad-hoc responses during crises.

Governed resilience introduces the concept of guardrails: minimum survivability standards, maximum acceptable dependency concentrations, and defined degradation rules. These guardrails do not eliminate risk, but they prevent uncontrolled exposure.

When resilience is governed, it becomes a managed capability rather than an after-action explanation.

Designing for Graceful Degradation

One of the most important implications of quantified resilience is a shift in design philosophy. Perfect continuity is rarely achievable. What matters is how systems fail.

Graceful degradation accepts that under severe stress, not all demand can be met. Instead, supply chains should be designed to prioritise critical outputs, preserve essential capabilities, and shed non-essential functions deliberately.

This requires tiered service models, modular substitution strategies, and clear prioritisation rules agreed in advance. When degradation is planned, recovery is faster and less damaging. When degradation is unplanned, failure cascades.

Resilience is not about avoiding failure altogether. It is about choosing how failure unfolds.

What Good Looks Like in 2026

Looking ahead, resilient organisations will distinguish themselves not by claims, but by evidence. By 2026, leading supply chains will routinely publish resilience metrics alongside financial results. They will stress-test their networks annually against defined scenarios. They will design contracts that reward survivability, not just efficiency.

Energy, data, logistics, and workforce considerations will be treated as coupled systems rather than independent variables. Leaders will understand not only where their supply chains are efficient, but where they are vulnerable, and why.

Most importantly, resilience discussions will move from storytelling to simulation, from assurance to analysis, from optimism to preparedness.

Conclusion: From Comfort to Credibility

Resilience has become a responsibility rather than a virtue. Responsibilities demand evidence. Evidence demands numbers.

As supply chains face a future defined by uncertainty rather than stability, the question is no longer whether resilience matters. The question is whether organisations are willing to measure it honestly.

The era of narrative resilience is ending. The era of quantified readiness must begin.

The most important question for leaders is not “Are we resilient?”

It is “How resilient are we — in numbers?”