By Paul R Salmon FCILT, FSCM, FCMI

Introduction: Why 2026 Is a Watershed Moment for Defence Supply Chains

For much of the post–Cold War era, defence supply chains were optimised for efficiency, cost control, and predictability. Logistics success was measured through inventory turns, contract performance, and unit cost reduction. That paradigm is no longer sufficient.

By 2026, defence supply chains will sit at the heart of national power, deterrence, and warfighting credibility. The combined impact of geopolitical instability, great-power competition, fragile global supply networks, digital dependence, and climate pressures has fundamentally reshaped the operating environment. Conflict in Ukraine, instability in the Red Sea, increasing Indo-Pacific tension, and the weaponisation of trade and energy have all reinforced one message: logistics is no longer a rear-area activity — it is a contested, strategic system.

For the UK, NATO, and allied forces, the supply chain is now inseparable from operational effectiveness. The ability to generate, sustain, and regenerate combat power depends as much on industrial resilience, data quality, and modelling confidence as it does on platforms and people. As we approach 2026, defence supply chains are undergoing a profound transition: from efficient support functions to adaptive, data-driven, warfighting enablers.

This article explores the key trends shaping defence supply chains in 2026, with a particular focus on UK Defence and NATO contexts, and outlines what senior leaders, logisticians, and policymakers must do to remain credible in an increasingly contested world.

1. Contested Logistics as the Design Baseline

Perhaps the most significant shift underway is the assumption that logistics will be contested from the outset of any future conflict. For decades, defence logistics planning implicitly assumed secure lines of communication, permissive host nations, and uncontested rear areas. Those assumptions are no longer valid.

By 2026, defence supply chains are increasingly designed on the basis that they will face:

physical interdiction of transport routes cyber attack against logistics systems and industrial partners denial of access to ports, airfields, and infrastructure disruption of commercial shipping and insurance markets information warfare targeting logistics confidence and decision-making

This reality is driving a shift from linear, hub-and-spoke supply models towards more distributed, resilient networks. Stockholding strategies are being reconsidered, with greater emphasis on forward resilience, dispersion, and rapid reconfiguration rather than centralised efficiency.

Logistics movements themselves are now treated as operational signatures. Fuel convoys, spare parts flows, and industrial dependencies all create vulnerabilities that adversaries can exploit. As a result, concealment, deception, and unpredictability are becoming as relevant to logistics planning as they are to manoeuvre.

In practical terms, this means defence supply chains in 2026 are being designed for degradation, disruption, and recovery, not steady-state optimisation.

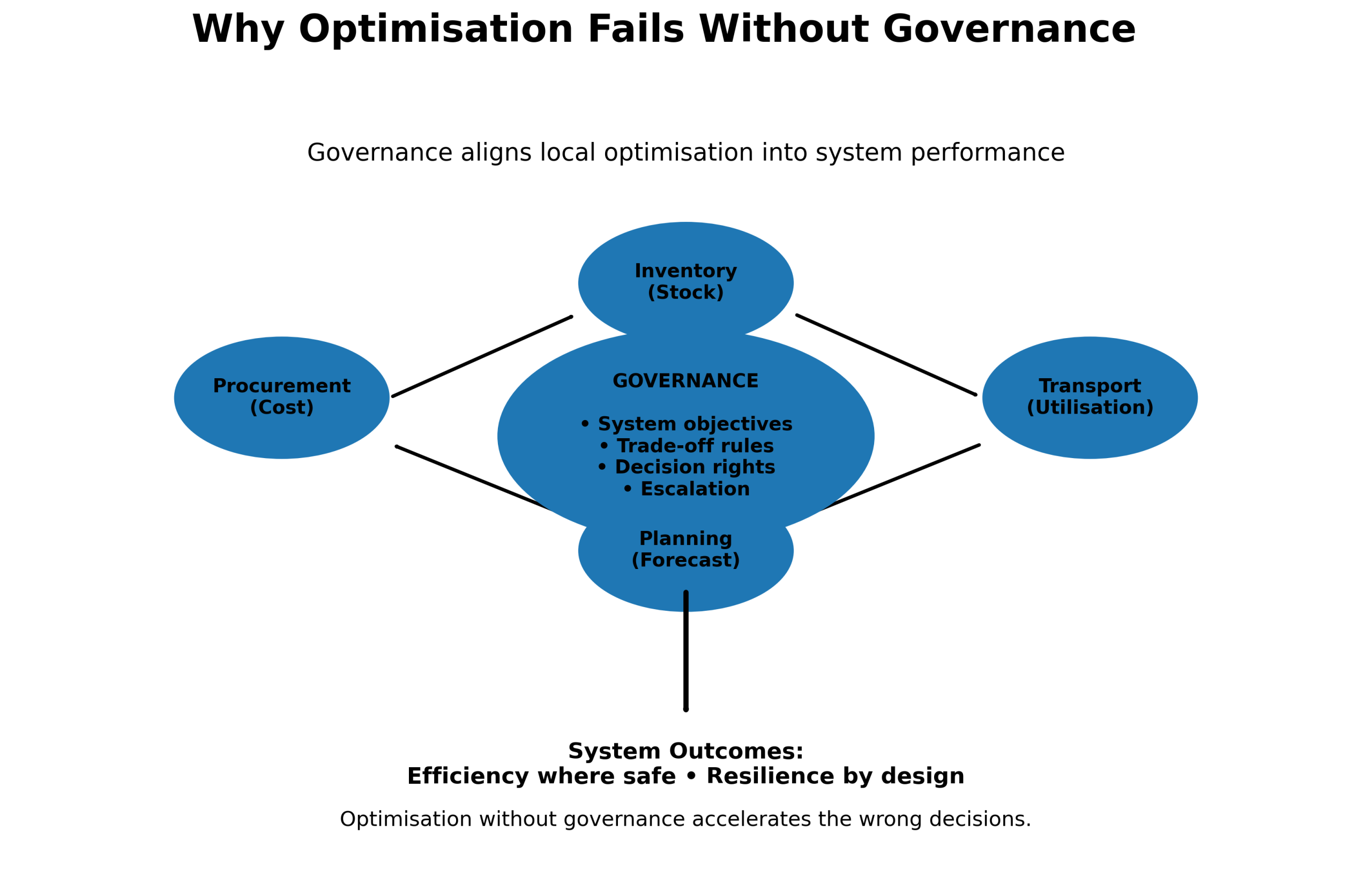

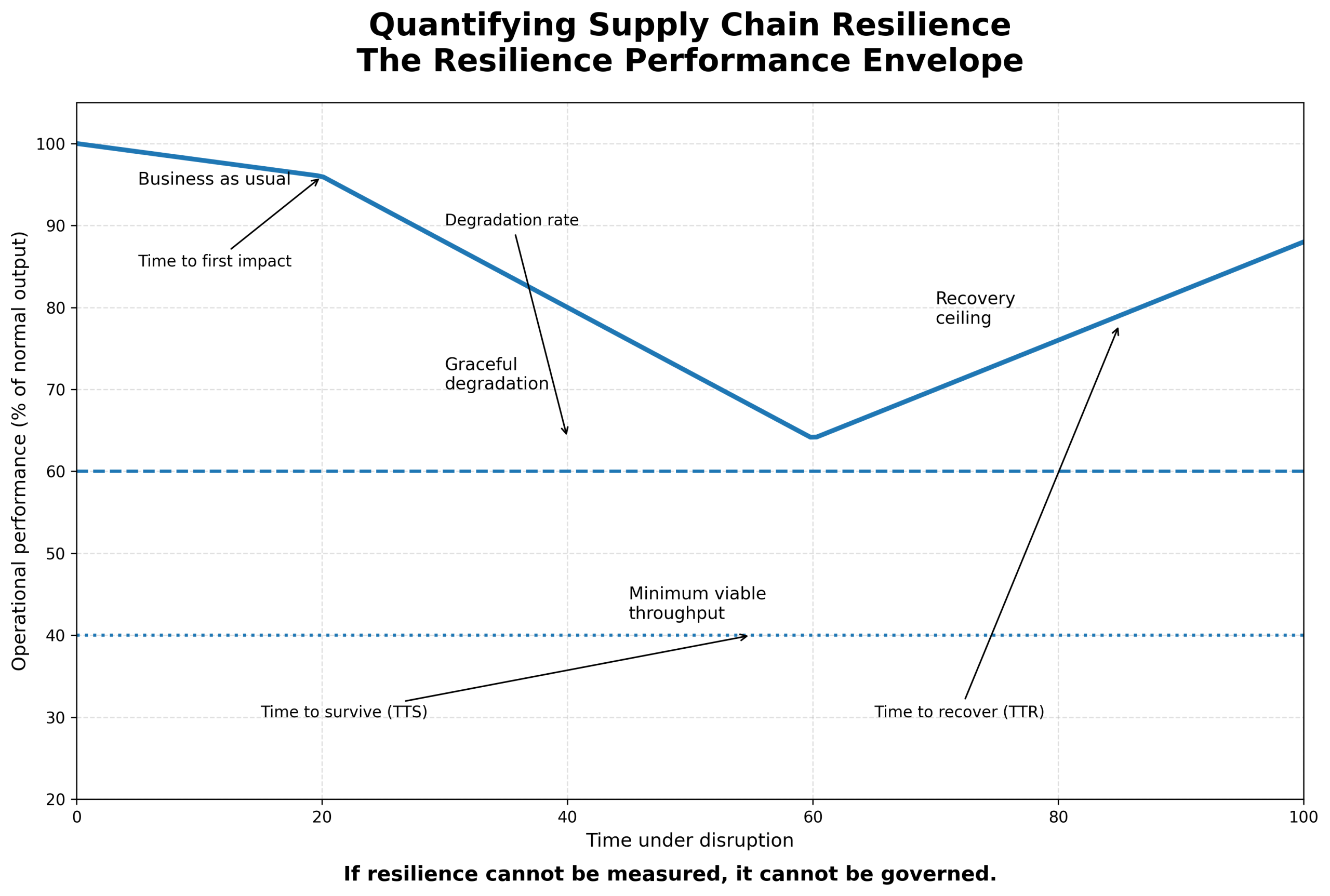

2. Resilience Replaces Efficiency as the Primary Objective

For many years, “efficiency” was treated as synonymous with “good logistics”. Lean inventories, single-supplier contracts, just-in-time delivery, and global sourcing were rewarded because they reduced cost. The last decade has exposed the fragility of that model.

By 2026, resilience has overtaken efficiency as the dominant design principle for defence supply chains. This does not mean cost is irrelevant — but it does mean cost is no longer the primary driver.

Resilience-focused supply chains exhibit several defining characteristics:

multiple sourcing pathways rather than single points of failure explicit consideration of substitution, repair, and cannibalisation options acceptance of some redundancy where operational risk demands it deliberate trade-offs between cost, availability, and recoverability

Crucially, resilience is no longer framed as a contingency or “insurance policy”. It is embedded into mainstream planning, approvals, and investment decisions. Business cases increasingly consider how quickly a system can recover from disruption, not just how cheaply it can operate in peacetime.

This shift also challenges traditional financial models. The value of resilience is often realised only when systems are stressed — but by 2026, defence organisations are becoming more comfortable justifying investment based on avoided operational risk, not just forecast savings.

3. Digital Twins and Modelling Move to the Centre of Decision-Making

One of the most important enablers of this transition is the maturation of digital twins and advanced modelling. Historically, modelling in defence logistics was often used retrospectively — to explain outcomes or support assurance after decisions had already been made.

By 2026, modelling and simulation are moving decisively upstream.

Digital twins of defence supply chains increasingly represent not just platforms or inventories, but complete support ecosystems: suppliers, repair loops, transport networks, workforce constraints, and policy assumptions. These models are used to test “what if” scenarios long before commitments are made.

Typical questions being explored include:

What happens to availability if a key industrial node is lost? How quickly can combat power be regenerated after attrition? What is the impact of switching suppliers under surge conditions? How does stock positioning affect operational tempo under attack?

This shift matters because it allows leaders to make decisions with a clearer understanding of risk, trade-offs, and second-order effects. It also creates a common analytical language between military planners, logisticians, engineers, commercial teams, and industry partners.

By 2026, defence organisations that cannot model their supply chains with confidence will struggle to justify decisions or respond at pace to emerging threats.

4. Data Quality as an Operational Risk

As defence supply chains become more digital, data quality becomes mission-critical. Poor data no longer simply creates inefficiency — it creates operational risk.

By 2026, leading defence organisations treat logistics data in the same way they treat safety-critical engineering data. Critical Data Elements (CDEs) are identified, governed, and assured because decisions on stock levels, readiness, and deployment depend on them.

This shift reframes data governance. It is no longer an IT or compliance activity; it is an operational necessity. Inaccurate demand data can result in under-stocking. Poor configuration data can undermine repair strategies. Incomplete supplier data can mask industrial fragility.

Commanders increasingly expect near-real-time logistics insight that is trustworthy, coherent, and decision-ready. This places new demands on data stewardship, standards, and accountability across defence and industry.

By 2026, organisations that cannot demonstrate confidence in their logistics data will find it difficult to support credible operational planning.

5. Industry as Part of the Force Structure

Another defining trend is the changing relationship between defence and industry. The traditional view of industry as an external supplier is giving way to a more integrated model in which industrial capacity is treated as part of the force structure.

Defence supply chains depend on complex networks of OEMs, SMEs, subcontractors, and service providers. In a contested environment, the availability of industrial capacity — skilled labour, tooling, materials, energy — becomes as important as military manpower.

By 2026, defence organisations increasingly seek:

greater transparency of supplier capacity and constraints earlier engagement with industry on readiness planning shared understanding of surge requirements and recovery timelines alignment between defence priorities and industrial investment decisions

This shift also has sovereign implications. Dependence on overseas suppliers for critical components, materials, or repair capability introduces strategic risk. As a result, defence supply chain strategy is increasingly linked to national industrial policy, skills pipelines, and energy resilience.

Industry is no longer simply “supporting” defence; it is embedded in the delivery of operational effect.

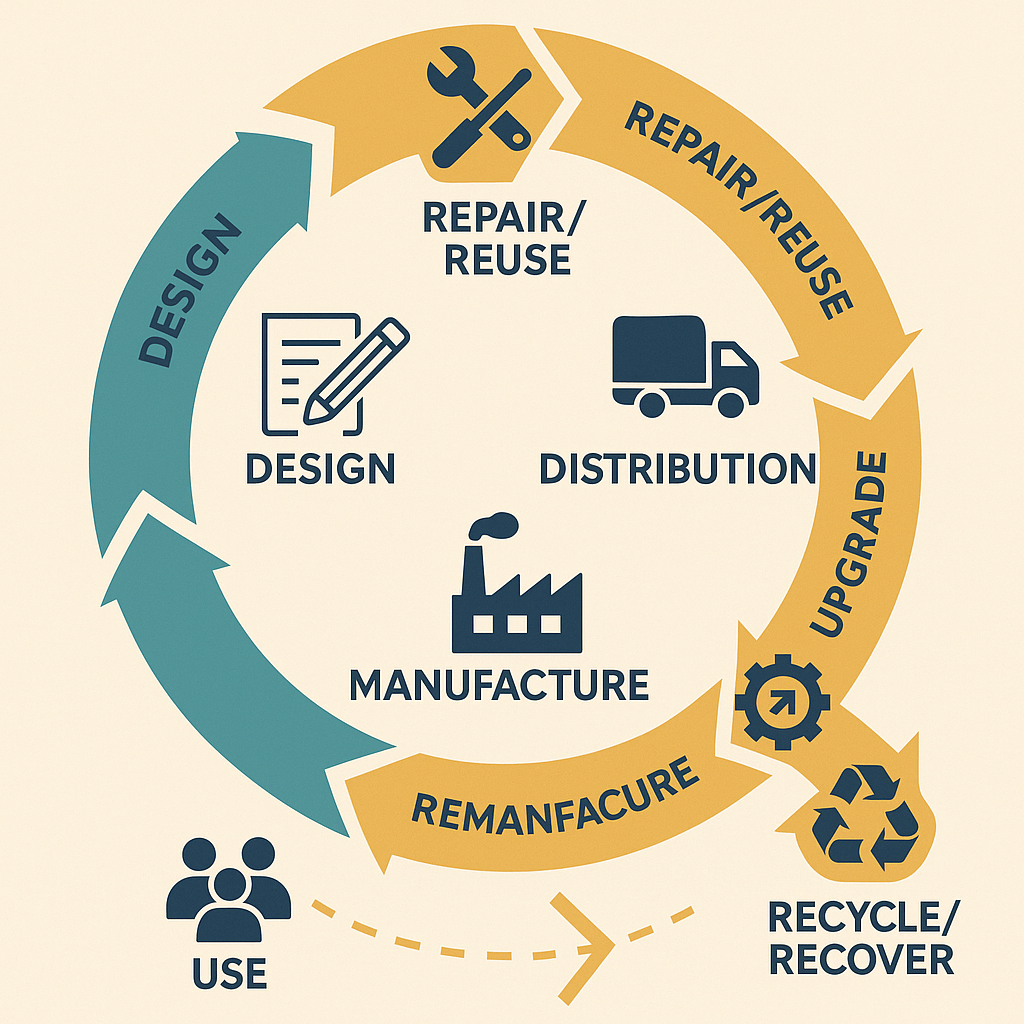

6. Sustainability as an Operational Enabler

In defence, sustainability is often misunderstood as a purely environmental or reputational issue. By 2026, that view is obsolete.

Energy demand, logistics burden, and environmental constraints directly affect operational freedom. Fuel consumption drives resupply frequency, which in turn increases vulnerability. Heavy, bespoke systems increase transport demand and reduce agility.

As a result, sustainability considerations are increasingly framed in operational terms:

reducing fuel demand reduces exposure to attack common systems reduce spare parts complexity repairable designs improve endurance and resilience circular approaches reduce dependency on fragile global supply chains

This does not mean defence is compromising capability for environmental reasons. Rather, sustainability is being recognised as a means of enhancing endurance, survivability, and adaptability in contested environments.

By 2026, sustainability is embedded into defence logistics as a contributor to combat effectiveness, not an external constraint.

7. Workforce Transformation: From Operators to Orchestrators

The defence logistics workforce is also changing rapidly. Automation, decision-support tools, and advanced analytics are reshaping roles and skills.

Routine planning tasks that once absorbed significant human effort are increasingly supported by digital tools. As a result, the value of the human workforce shifts towards judgement, integration, and orchestration.

By 2026, successful defence logisticians are expected to:

understand complex systems and trade-offs interpret model outputs critically manage uncertainty and risk integrate military intent with industrial reality

This places new demands on professional development. Data literacy, modelling awareness, and systems thinking become core competencies, alongside traditional operational experience.

Importantly, this does not diminish the importance of human judgement. In fact, as systems become more complex, the need for informed, accountable decision-makers increases. Technology supports decisions; it does not replace responsibility.

8. Artificial Intelligence with Human Authority

Artificial intelligence is increasingly present in defence logistics — but its adoption is deliberately cautious.

By 2026, AI is widely used for demand sensing, pattern recognition, anomaly detection, and option generation. It helps identify emerging risks, optimise routing, and highlight inefficiencies faster than human teams alone could manage.

However, defence remains clear-eyed about the limits of automation. Decisions with lethal, strategic, or alliance implications remain firmly under human authority. The prevailing model is human-on-the-loop, not human-out-of-the-loop.

This balance reflects both ethical considerations and operational reality. AI can process vast amounts of data, but it does not understand intent, escalation dynamics, or political context. Defence supply chains in 2026 use AI to enhance judgement, not replace it.

9. New Metrics for a New Reality

As priorities change, so do performance measures. Traditional logistics KPIs — on-time delivery, stock availability, cost variance — remain relevant, but they are no longer sufficient.

By 2026, defence organisations increasingly track metrics such as:

time to regenerate combat power time to recover from supply disruption substitution and interchangeability viability repair versus replacement ratios industrial surge readiness

These metrics better reflect operational risk and resilience rather than peacetime efficiency. They also support more informed dialogue between military leaders, logisticians, and policymakers about acceptable risk.

What gets measured drives behaviour. By redefining success, defence supply chains are reshaping how decisions are made.

10. NATO and Allied Interoperability at Scale

Finally, 2026 sees accelerated progress in allied interoperability. Defence supply chains rarely operate in isolation; coalition operations are the norm, not the exception.

Interoperability increasingly extends beyond equipment compatibility to include:

shared logistics data standards common approaches to stock visibility mutual support arrangements interoperable repair and sustainment concepts

The aim is not uniformity, but compatibility under pressure. Supply chains must be able to plug together, share capacity, and adapt collectively when systems are stressed.

This is both a technical and cultural challenge, but by 2026 it is recognised as essential to credible deterrence and collective defence.

Conclusion: Logistics as a Strategic Weapon

By 2026, defence supply chains are no longer background systems quietly enabling operations. They are strategic assets that shape deterrence, resilience, and warfighting credibility.

The shift underway is profound. Efficiency gives way to resilience. Static plans give way to adaptive systems. Data, modelling, and industry integration become central to operational success.

For the UK and its allies, the lesson is clear: logistics is not simply about moving and storing things — it is about sustaining power under pressure.

Those defence organisations that invest now in resilient supply chain design, trusted data, skilled people, and integrated industry partnerships will be better prepared for an uncertain future. Those that do not risk discovering, too late, that operational ambition outpaced logistical reality.

In the emerging security environment, supply chains do not just support strategy — they are strategy.