By Paul R. Salmon FCILT, FSCM, FCMI

Introduction: Why Adaptive Capacity Matters

Modern defence supply chains face an era of relentless volatility. Geopolitical tensions, climate shocks, cyber vulnerabilities, fragile industrial bases, and skills shortages have converged to create an operating environment where the “known” is increasingly rare and the “unexpected” is routine.

In this environment, adaptive capacity has become a defining characteristic of resilient organisations. At its simplest, adaptive capacity is the ability to anticipate, absorb, and respond to disruption while continuing to operate effectively. In commercial sectors, firms with adaptive supply chains outpace competitors in both profitability and survival. For Defence, the stakes are higher: adaptive capacity is nothing less than the foundation of warfighting readiness and national resilience.

The UK Armed Forces, supported by Defence Equipment & Support (DE&S) and the wider logistics ecosystem, must now evolve from a model designed for predictability and efficiency to one built on flexibility, redundancy, and recovery. This article explores how adaptive capacity can be embedded into UK Defence support, drawing on historical lessons, current challenges, and future opportunities.

Defining Adaptive Capacity in Defence

While resilience and adaptability are often used interchangeably, adaptive capacity is a distinct concept:

Resilience is the ability to withstand shocks. Adaptability is the ability to change course. Adaptive capacity combines both: the structural, cultural, and technical ability to respond effectively to uncertainty and emerge stronger.

In Defence, this translates into a support system that:

Can absorb a sudden surge in demand without collapse. Can reconfigure supply routes, contracts, or support models in response to disruption. Can learn quickly from disruption, embedding new approaches into doctrine and practice.

Why Defence Supply Chains Are Vulnerable

Adaptive capacity matters most where fragility is greatest. UK Defence faces four major sources of vulnerability:

Geopolitical Contestation Global supply chains are increasingly shaped by great-power competition. Access to critical minerals, energy, and strategic materials is contested. Reliance on single-country sources (e.g., rare earths from China) creates strategic risk. Industrial Fragility Decades of just-in-time efficiency have hollowed out redundancy in commercial supply chains. Defence depends on the same industrial base, competing with civilian demand for limited capacity in areas like semiconductors, precision machining, and shipping. Climate and Environmental Risk Climate change disrupts logistics through port closures, flooding, wildfires, and extreme weather events. Defence supply routes and bases, many coastal, are particularly exposed. Skills Shortages Defence support relies on logisticians, engineers, data analysts, and supply chain managers. Across industry, these skills are in short supply. Without professionalisation and career pathways, Defence risks falling behind.

Lessons from History

History demonstrates that adaptive capacity has always determined military outcomes.

The Desert Campaigns of WWII: Logistics lines stretched across vast deserts required adaptive use of captured enemy fuel, rapid repair of vehicles, and improvised depots. Commanders who adapted survived; those who clung to rigid plans faltered. Falklands War (1982): With supply lines 8,000 miles long, adaptive planning was vital. Civilian shipping was requisitioned and rapidly repurposed (STUFT – Ships Taken Up From Trade). Without this surge capacity, the campaign would not have been sustained. Operation Telic (Iraq, 2003): Initial shortages of desert-ready equipment highlighted the limits of static planning. Over time, adaptive partnerships with suppliers and rapid contracting mechanisms allowed the force to stabilise.

These lessons reinforce a single truth: no plan survives first contact with reality unless the support system is designed to adapt.

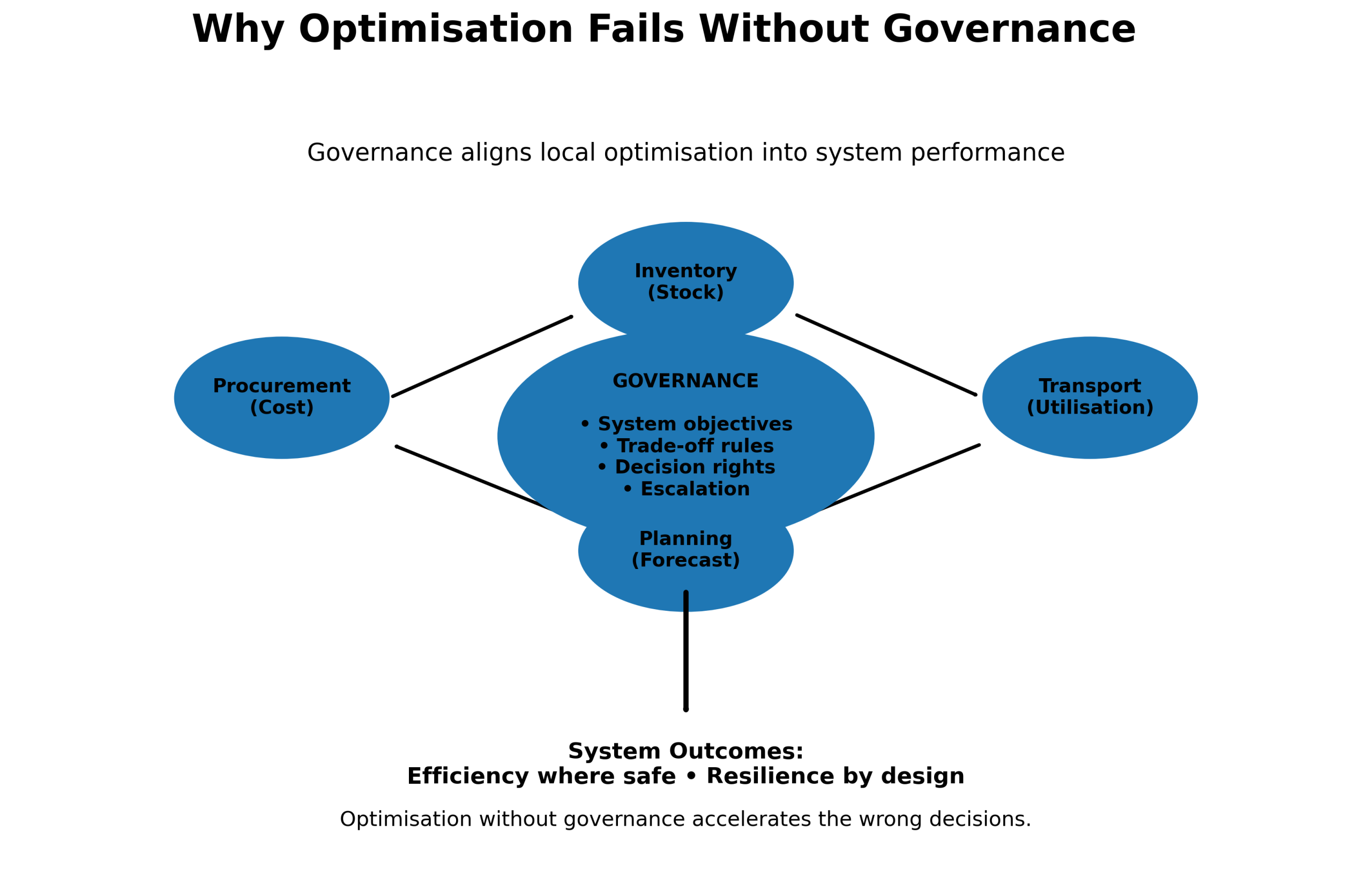

Building Blocks of Adaptive Capacity

For UK Defence to strengthen adaptive capacity, five building blocks must be embedded into the support system.

1. Data-Driven Visibility

Without visibility, there is no adaptability. Defence must move from fragmented data systems to a single source of truth for asset, inventory, and workforce data.

Predictive Analytics: AI-driven demand forecasting to anticipate surges before they occur. Digital Twins: Simulation of supply chains under stress to test response options. Common Dashboards: One support cost and availability picture, shared across MOD, DE&S, and front-line commands.

2. Flexible and Redundant Supply Networks

Adaptive capacity requires choice: multiple suppliers, multiple routes, and the ability to switch seamlessly.

Multi-sourcing Critical Items: Avoid single points of failure in rare earths, semiconductors, and munitions. Allied Interoperability: Shared spares pools with NATO partners, reducing duplication and increasing surge depth. Civil–Military Integration: Building contracts with civilian hauliers, shipping lines, and port operators into contingency plans.

3. Modular and Scalable Support

Static contracts and fixed infrastructure limit adaptability. Support must become modular.

Agile Contracting: Frameworks that can scale up or down quickly. Deployable Logistics Modules: Containerised workshops, fuel depots, and mobile medical units. 3D Printing: Additive manufacturing hubs co-located with deployed forces.

4. Skills and Professionalisation

Adaptive capacity is not only about systems but about people.

Professional Accreditation: Embedding CILT and other professional standards into Defence career pathways. Cross-Training: Multi-skilled logisticians able to flex between roles. Citizen Data Scientists: Training logisticians to use AI and analytics tools without waiting for specialists.

5. Innovation and Learning Culture

Finally, adaptive capacity depends on culture. A rigid, risk-averse mindset limits options.

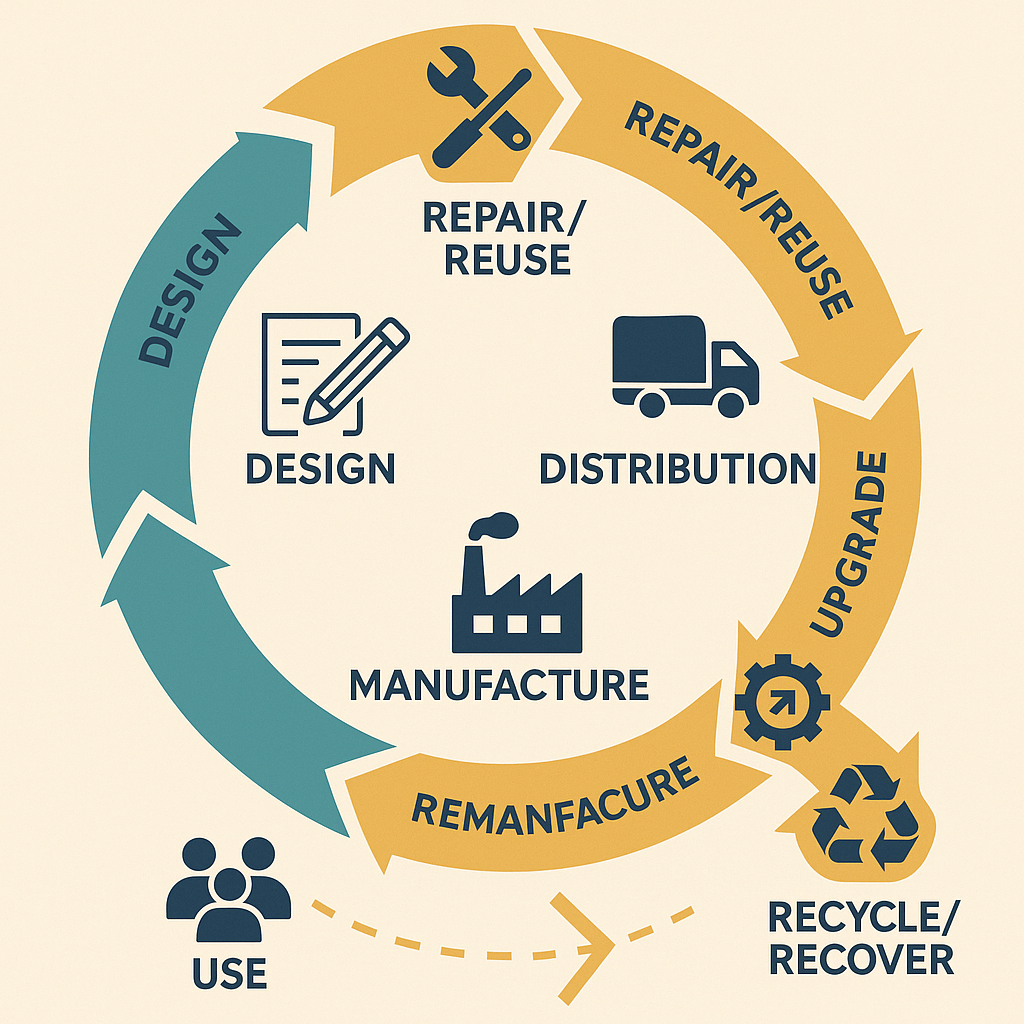

Rapid Experimentation: Trialling new logistics models in exercises before crises. Circular Economy: Re-using materials, remanufacturing spares, recycling metals (e.g., Tornado to Tempest titanium). After-Action Learning: Embedding lessons quickly into doctrine and training.

Partnerships for Adaptive Capacity

UK Defence cannot achieve adaptive capacity alone. Partnerships are central:

With Industry: Organisations like Logistics UK bring visibility of commercial capacity and workforce development. With Professional Bodies: CILT provides frameworks for accreditation, CPD, and professional standards. With Allies: NATO interoperability ensures Defence is never isolated in crisis. With Academia: Research into AI forecasting, climate resilience, and supply chain modelling drives innovation.

A Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) between UK Defence and Logistics UK could institutionalise these partnerships, creating joint programmes on skills, adaptive supply chain modelling, and national resilience planning.

Adaptive Capacity in Practice: Case Examples

COVID-19 Response (2020) Defence played a critical role in PPE and vaccine distribution. Rapid surge of military logistics alongside NHS and industry demonstrated adaptive contracting and distribution at national scale. Ukraine Support (2022–present) UK supply chains adapted to sustain both domestic readiness and international commitments. Lessons include the importance of stockpiling, industrial partnerships, and accelerated procurement routes. Climate Stress Scenarios Simulations show that flooding at key UK ports (e.g., Felixstowe, Portsmouth) could disrupt operations. Adaptive routing via alternative ports and collaboration with civilian shipping are now built into contingency planning.

Risks of Not Investing in Adaptive Capacity

Failure to embed adaptive capacity carries stark risks:

Operational Failure: Units grounded due to missing consumables or spares. Strategic Dependence: Over-reliance on single suppliers or nations, reducing sovereignty. Industrial Collapse: Inability to scale production when demand spikes. Erosion of Trust: Between Defence, Government, and the public when supply failures undermine credibility.

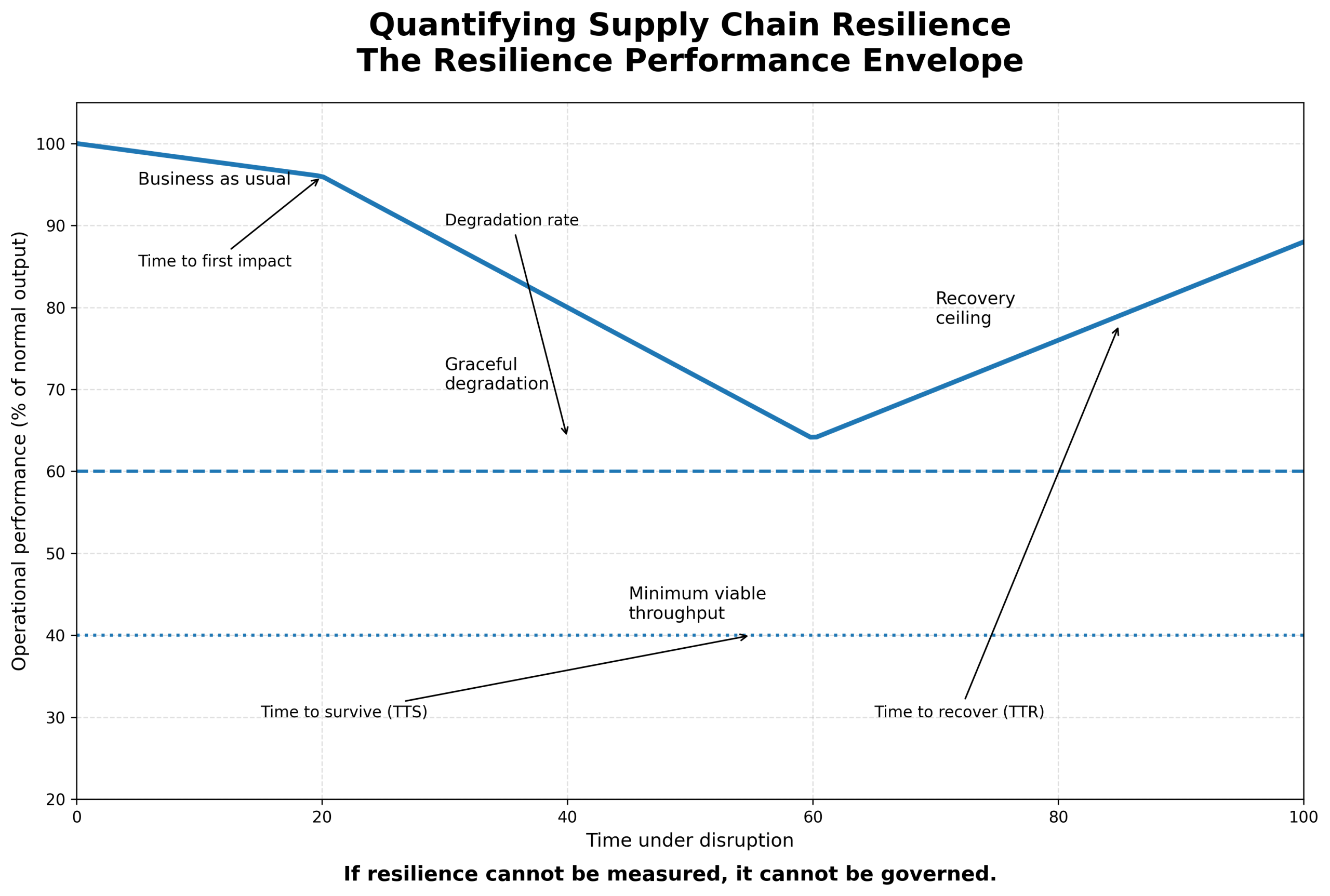

Towards a Defence Logistics Adaptive Capacity Index

To measure progress, Defence could establish a Logistics Adaptive Capacity Index (LACI). This would assess:

Supply Chain Redundancy: Diversity of suppliers and routes. Data Maturity: Availability of predictive tools and shared dashboards. Skills Depth: Percentage of workforce with accredited logistics qualifications. Innovation Adoption: Use of additive manufacturing, circular economy practices. Stress-Test Performance: Results of war-games and simulations.

A transparent index, reported annually, would drive accountability and improvement.

Conclusion: Adaptive Capacity as a Strategic Imperative

Adaptive capacity is no longer optional for UK Defence — it is the defining factor in whether our support system can deliver warfighting readiness in an age of uncertainty.

Embedding adaptive capacity requires investment in data, flexible networks, modular support, professional skills, and innovative culture. It requires partnerships with industry, allies, and professional bodies. And it requires a clear framework for measuring and reporting progress.

If the UK Armed Forces are to deter adversaries, reassure allies, and respond to crises — from high-intensity conflict to humanitarian relief — the support system must be able to bend without breaking, recover without delay, and learn without hesitation.

Adaptive capacity is not just a logistician’s concern. It is a strategic national asset, central to defence, prosperity, and resilience in the 21st century.

Leave a Reply