By Paul R Salmon FCILT, FSCM

In too many organisations, engineers and logistics professionals work side by side yet rarely engage deeply. One group designs cutting-edge systems and products; the other ensures those same systems are transported, stored, maintained, and delivered to the right place at the right time. Both are critical to success.

But when they don’t talk—or talk too late—the supply chain suffers.

So, what happens when engineers and logisticians actually collaborate? The answer: smarter designs, leaner supply chains, and reduced costs.

Smarter Designs: Build for Supportability

In the civilian world, Tesla’s Gigafactory redefined how engineering and logistics teams collaborate. Engineers were embedded with logistics teams during the early design stages of battery packs, ensuring they could be transported safely and efficiently across continents. This alignment meant fewer wasted materials, more efficient containerisation, and faster time-to-market.

Contrast that with a defence example: a newly fielded UAV was designed with no consideration for how its oversized wings would fit into standard RAF C-17 cargo aircraft. As a result, an expensive bespoke container had to be built, and deployment times increased by weeks. If logisticians had been involved earlier, the design could have featured folding wings or modular components to make transport straightforward.

Lower Costs and Carbon: The Space Factor

Every additional centimetre in product size can cascade into wasted space in trucks, ships, and warehouses. One defence programme discovered that a minor design change—a sensor mounting bracket extended by just 50mm—meant the packaged unit no longer fit on standard NATO pallets. The result? 30% fewer units per load, higher transport costs, and increased carbon emissions.

In the commercial sector, IKEA’s flat-pack design philosophy is legendary for integrating logistics thinking into engineering from the start. Designers are challenged to minimise empty space in shipping containers, cutting CO2 emissions and enabling lower pricing for customers.

Imagine if defence systems were designed with the same discipline.

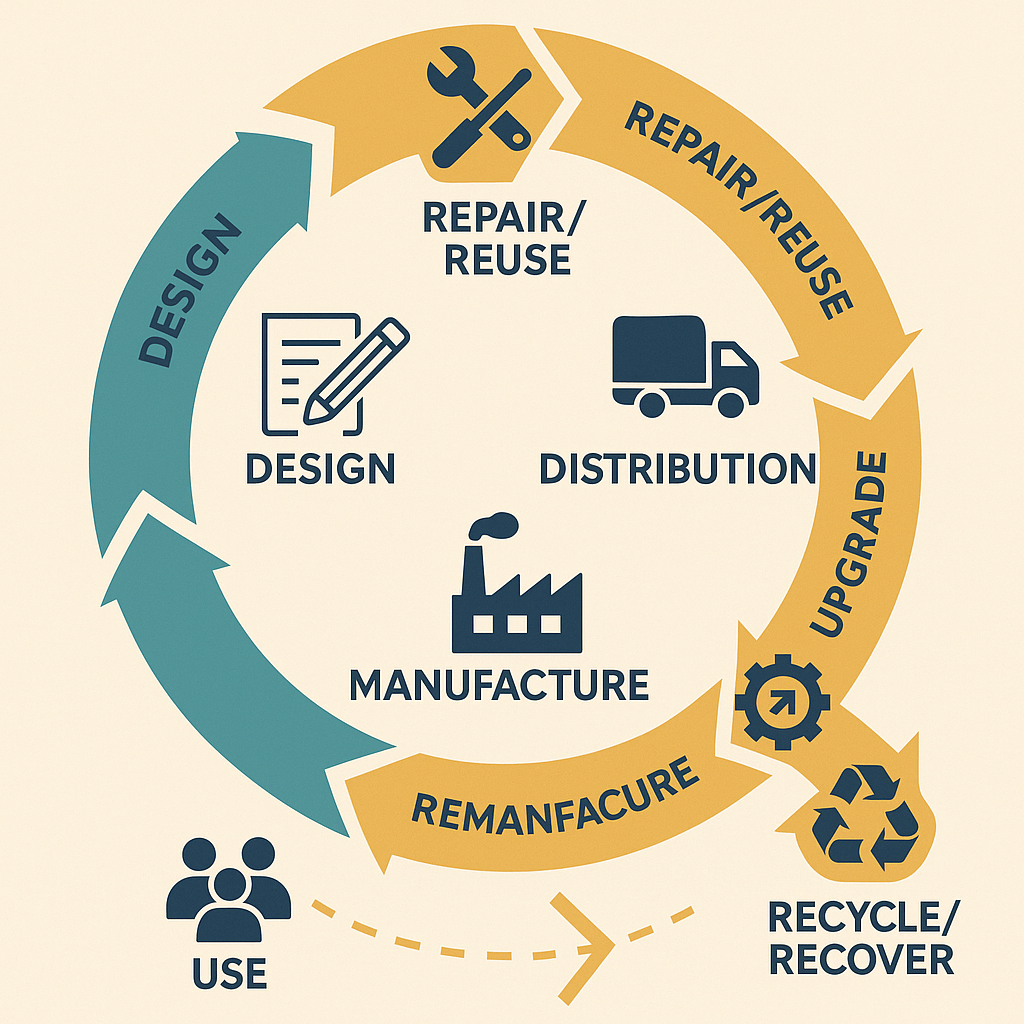

Better Availability: Commonality and Interchangeability

Defence support chains are notorious for being clogged with unique, platform-specific parts. One NATO logistics team described receiving 30 different variants of the same type of bolt—each requiring its own storage and tracking—because different engineering teams specified slightly different standards.

When engineers and logisticians collaborate, they can drive commonality: using shared parts across platforms to simplify supply chains. The US Army’s Joint Light Tactical Vehicle programme is a positive example, where logistics input early in the design process reduced the number of unique spare parts by 40%.

In the civilian world, automotive companies like Toyota design for interchangeability across models, meaning fewer parts need to be stocked globally. This saves millions in inventory costs and improves repair times.

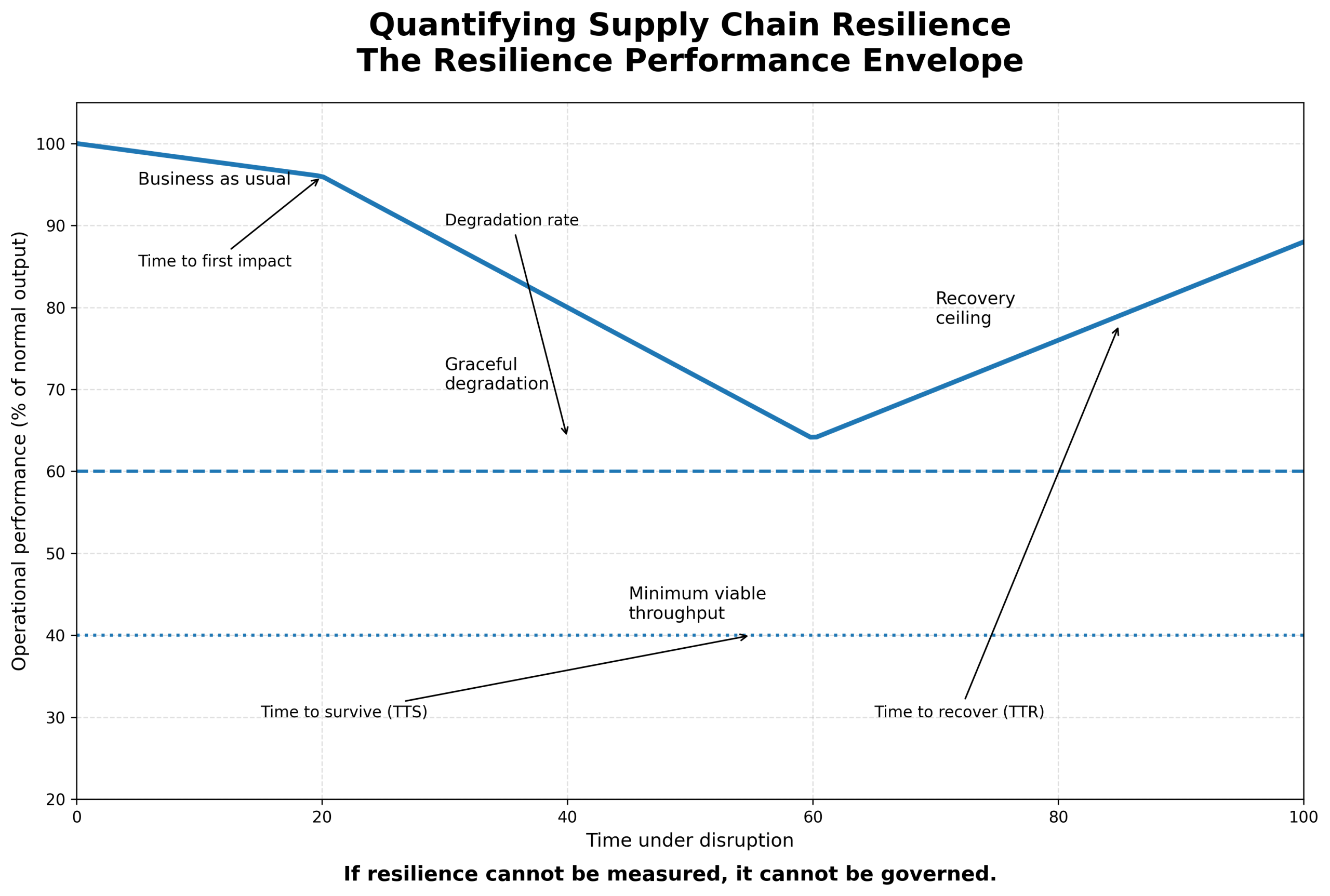

Resilient Supply Chains: Designing for Disruption

Geopolitical instability, pandemics, and climate shocks have made supply chain resilience a boardroom priority. But resilience isn’t just about logistics—it starts with design.

An aircraft designed for rapid deployment can become a logistics nightmare if it requires temperature-controlled containers that can’t be sourced at short notice. Similarly, a medical device manufacturer learned the hard way during COVID-19 that its components relied on a single supplier in Wuhan. The engineers and supply chain team had never mapped out this dependency together.

If these conversations had taken place earlier, alternate materials or dual-sourcing could have been built into the design.

Why Don’t They Talk?

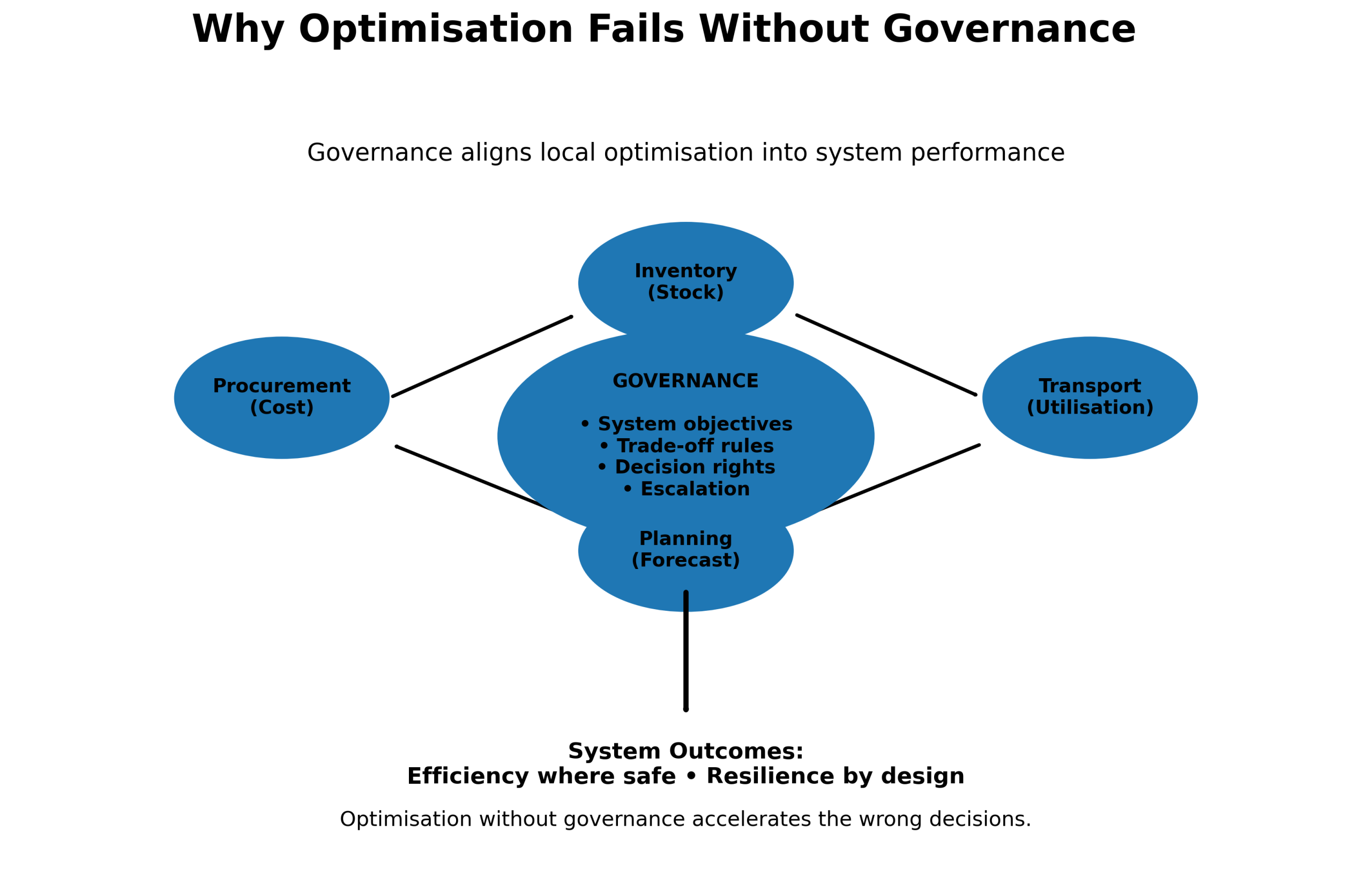

The gap between engineering and logistics isn’t about bad intent—it’s about silos. Engineers are incentivised to design for performance and innovation. Logisticians are measured on cost, speed, and reliability. These priorities can feel in tension.

In many organisations, there’s no structured way to bring these teams together. Decisions about packaging, transportability, and supportability often happen after designs are locked, when changes are expensive or impossible.

Bridging the Divide

Forward-thinking organisations are showing how to bridge this gap:

✅ Cross-Functional Design Teams: Embedding logisticians alongside engineers during design phases ensures supportability considerations are baked in.

✅ Design for Logistics (DfL): A formal process that challenges engineering teams to consider packaging, transport, and sustainment from day one.

✅ Digital Twins: In defence, digital twins are enabling joint engineering-logistics planning, allowing teams to simulate supply chain impacts of design choices in real time.

✅ Cultural Change: Perhaps most importantly, organisations need to reward cross-functional collaboration, not just individual technical brilliance.

The Call to Action

If only engineers and logisticians talked earlier, supply chains would be leaner, greener, and far more resilient.

In today’s complex world—whether fielding a new fighter jet or launching the next consumer electronics product—supportability isn’t a “nice-to-have.” It’s a critical design parameter.

Next time you hear an engineer say, “Just get it delivered,” or a logistician groan, “Who designed this thing?”, ask: could this have been avoided with a conversation?

The best supply chains don’t happen by accident. They are designed—together.