By Paul Salmon FCILT, FSCM

Introduction – The Unequal World of Supply Chains

Every product has a supply chain, but not all chains are equal. Some are short, local, and relatively simple — think of a village bakery sourcing flour from a nearby mill. Others stretch across the globe, weaving together thousands of suppliers, multiple regulatory frameworks, and decades-long life cycles.

The question of which items have the longest and most complex supply chains is more than academic. It shines a light on the fragility, resilience, and interdependence of our modern world. From fighter jets to pharmaceuticals, from smartphones to coffee beans, complexity varies by product type — but the lessons are universal.

1. Aerospace Systems – Millions of Parts, Decades of Support

Few supply chains rival aerospace in terms of sheer length and complexity. A single commercial airliner can contain 3–4 million individual parts, each sourced from multiple suppliers and countries.

Global spread: Boeing’s 787 Dreamliner includes components from Japan (wings), Italy (fuselage sections), the UK (landing gear), and the US (avionics). Lead times: Aircraft engines alone can take 18–24 months to manufacture. Support lifecycle: An aircraft may fly for 30–40 years, requiring spare parts, upgrades, and maintenance long after the original suppliers have moved on. Regulatory complexity: Aviation requires strict safety certification at every stage, adding layers of oversight.

This combination of long time horizons, global interdependence, and zero tolerance for error makes aerospace supply chains some of the most complex in the world.

2. Pharmaceuticals and Vaccines – Science Meets Fragility

The pharmaceutical industry offers another contender for the title. A single medicine may involve hundreds of production steps, sourced across multiple continents.

Inputs: Active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) may be produced in India, excipients in Europe, and packaging materials in Asia. Specialised requirements: Some vaccines require ultra-cold storage (-70°C for Pfizer’s COVID-19 vaccine), making logistics as complex as manufacturing. Regulation: Every batch must meet stringent compliance standards in every jurisdiction. Fragility: Delays in a single raw material can halt entire global vaccination programmes.

The COVID-19 pandemic exposed just how interdependent pharmaceutical supply chains are — and how they are both lifesaving and vulnerable.

3. Electronics and Smartphones – A Web of Rare Earths and Assembly Lines

Modern electronics embody supply chain globalisation. A smartphone, for example, integrates over 200 suppliers across more than 40 countries.

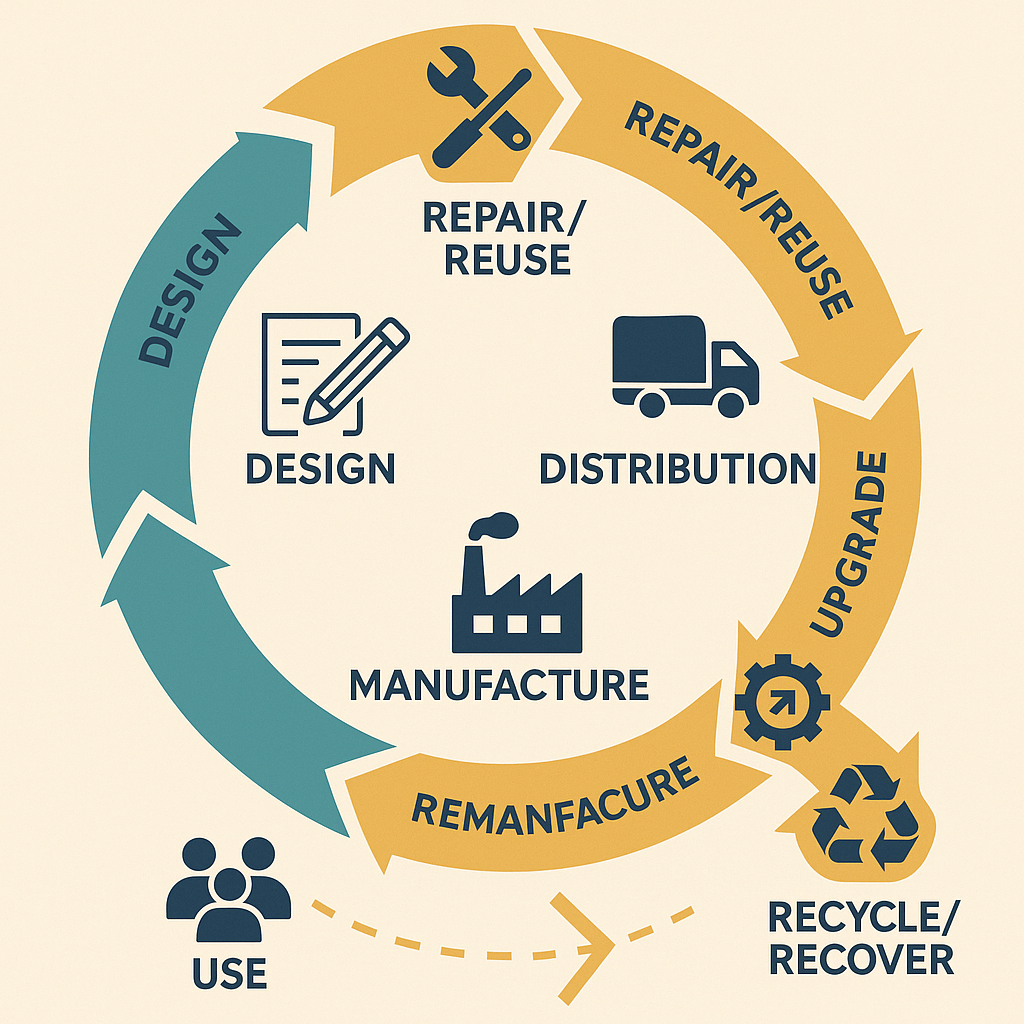

Raw materials: Rare earth metals from China, cobalt from the Democratic Republic of Congo, lithium from South America. Components: Chips from Taiwan, displays from South Korea, sensors from Japan. Assembly: Often centralised in China or Vietnam. Aftermarket: Repairs, recycling, and resale extend the chain even further.

Electronics chains are also highly fragile. The 2020–21 semiconductor shortage highlighted how dependence on a handful of fabs (notably TSMC in Taiwan) can paralyse entire industries, from automotive to consumer tech.

4. Defence Supply Chains – Complexity with National Security Stakes

Defence platforms — such as submarines, fighter jets, or satellites — may not move in high volumes like smartphones, but their depth of complexity is unmatched.

Longevity: Programmes like the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter span 50+ years, from design to retirement. Global sourcing: The F-35 involves 1,400 suppliers across 9 nations, with strict export controls dictating flows. Obsolescence management: Parts must be supported long after commercial suppliers exit the market. Political overlay: Procurement is as much about alliances and diplomacy as logistics.

Unlike consumer goods, failure in a defence supply chain isn’t measured in lost sales — it can mean lost capability, with direct implications for national security.

5. Food and Agriculture – Millions of Farmers, Billions of Cups

Not all complexity is industrial. Food and agriculture chains — particularly for commodities like coffee and chocolate — are equally intricate.

Scale: Coffee involves 25 million smallholder farmers across Africa, Asia, and Latin America. Intermediaries: Beans pass through cooperatives, exporters, traders, roasters, distributors, and finally retailers. Vulnerability: Entire harvests are subject to climate change, pests, or price swings. Ethical dimension: Labour conditions, child exploitation, and sustainability certification add layers of oversight.

The “cup of coffee” supply chain shows complexity at the social and environmental level, not just the technical or regulatory.

Measuring Complexity – What Makes a Chain ‘Longest’?

So which is longest and most complex? It depends on the dimension we value most:

By parts count: Aerospace wins, with millions of components. By fragility: Pharmaceuticals, where one missing ingredient halts production. By global spread: Electronics, with dozens of countries integrated into one device. By politics and time horizon: Defence, with half-century lifecycles and multinational interdependencies. By human scale: Food, involving millions of vulnerable producers.

In truth, there is no single winner. Each sector demonstrates a different flavour of complexity — technical, social, geopolitical, or regulatory.

Lessons for Supply Chain Leaders

What unites these diverse examples is not their differences, but their shared lessons:

Interdependence is the norm. No industry is an island; disruption in one part of the chain ripples across the world. Transparency is critical. From counterfeit wine to pharma quality standards, trust is built on traceability. Resilience beats efficiency. Lean just-in-time models are ill-suited to aerospace, defence, or vaccines where lives and safety are at stake. Sustainability is rising. Whether in electronics mining, coffee farming, or aircraft emissions, green pressures are reshaping chains. Technology is double-edged. AI, blockchain, and sensors offer solutions but also add complexity and dependency.

Conclusion – Managing the Longest Chains

The longest and most complex supply chains are not defined by kilometres or parts alone, but by the intersection of geography, regulation, politics, and time. Aerospace, pharmaceuticals, electronics, defence, and food each reveal a different dimension of what “complexity” means.

For today’s supply chain leaders, the challenge is not to eliminate complexity — that is impossible. It is to manage it intelligently: building resilience without waste, transparency without bureaucracy, and sustainability without sacrificing performance.

Not all supply chains are created equal — but all demand careful stewardship.

Word count: ~1,970