By Paul R Salmon FCILT FSCM FCMI

Chair, CILT Defence Forum

⸻

Introduction

Modern military success hinges not only on superior strategy and combat capability, but on logistics systems that can deliver under pressure. The ability to sustain operations at scale, over time, and in uncertain environments is often the decisive factor in operational effectiveness.

At the heart of that capability is supply chain capacity modelling—a vital discipline that ensures our Armed Forces can meet demand with the right resources, at the right time, in the right place.

For UK Defence, operating in increasingly contested and coalition-led environments such as NATO, this discipline is no longer optional—it’s fundamental. As Defence Support continues to modernise, capacity modelling is emerging as the linchpin that links ambition with realistic delivery.

⸻

What is Supply Chain Capacity Modelling?

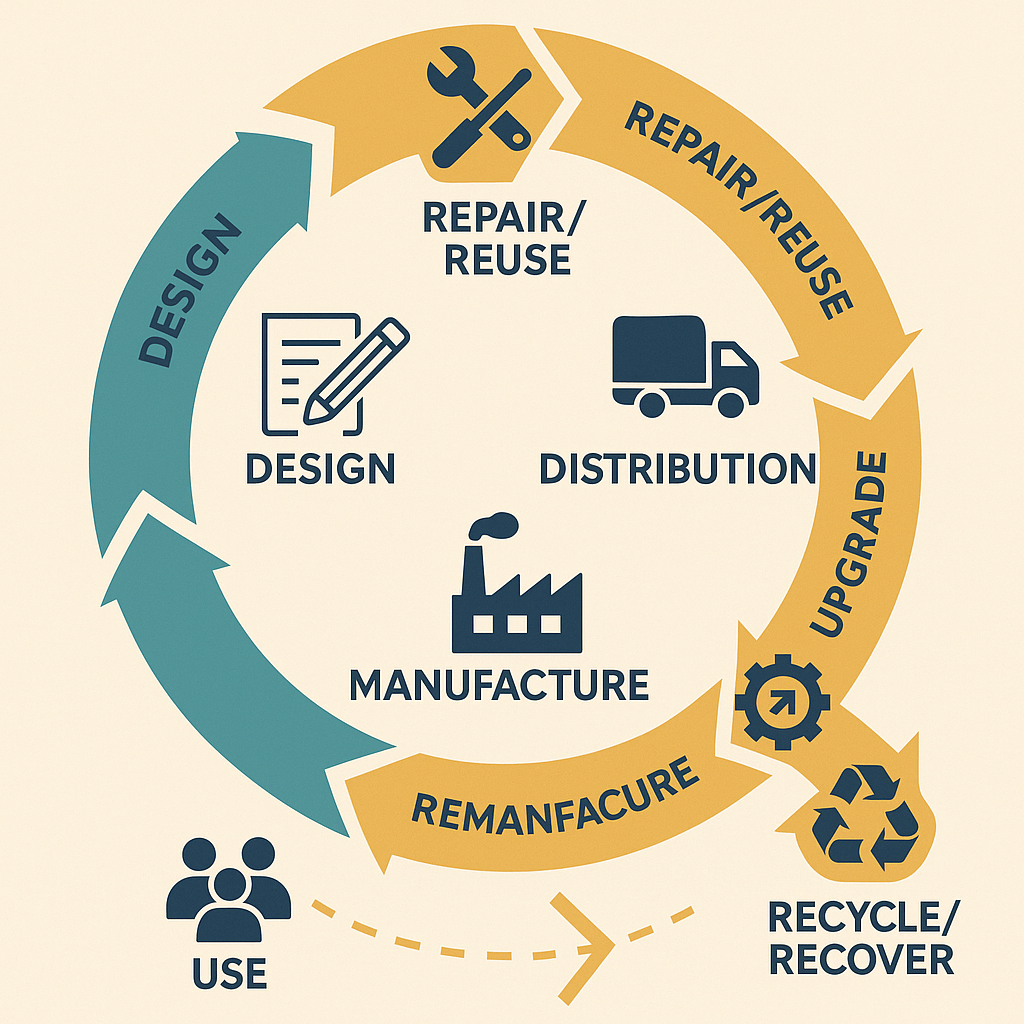

In simple terms, capacity modelling is the process of understanding and forecasting the limits of a supply chain’s performance under varying conditions. It quantifies how much can be produced, transported, stored, repaired, or delivered—based on existing infrastructure, personnel, equipment, and processes.

But it goes further: capacity modelling explores how the system will behave under pressure, what happens when demand surges, where constraints lie, and how interventions can change the outcome.

⸻

Why It Matters for UK Defence

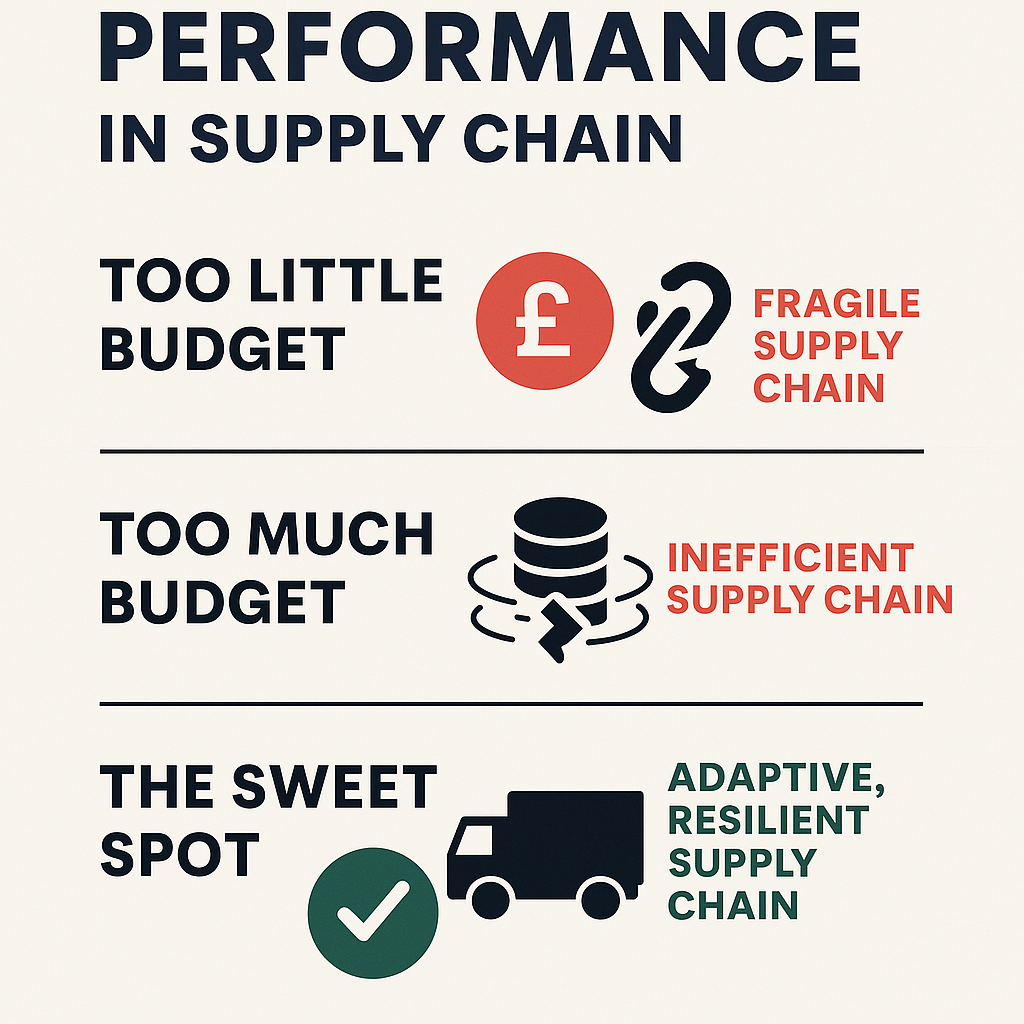

1. Beyond Planning—Predicting Survivability

In Defence, supply chains must do more than fulfil routine demand—they must endure shock, scale rapidly, and recover fast. This requires an understanding of latent and surge capacity. If planners don’t model these thresholds, decisions are made blind, and operational effectiveness is compromised.

For example, consider:

• The number of pallet spaces at a strategic distribution hub.

• The transport uplift available to move equipment during mobilisation.

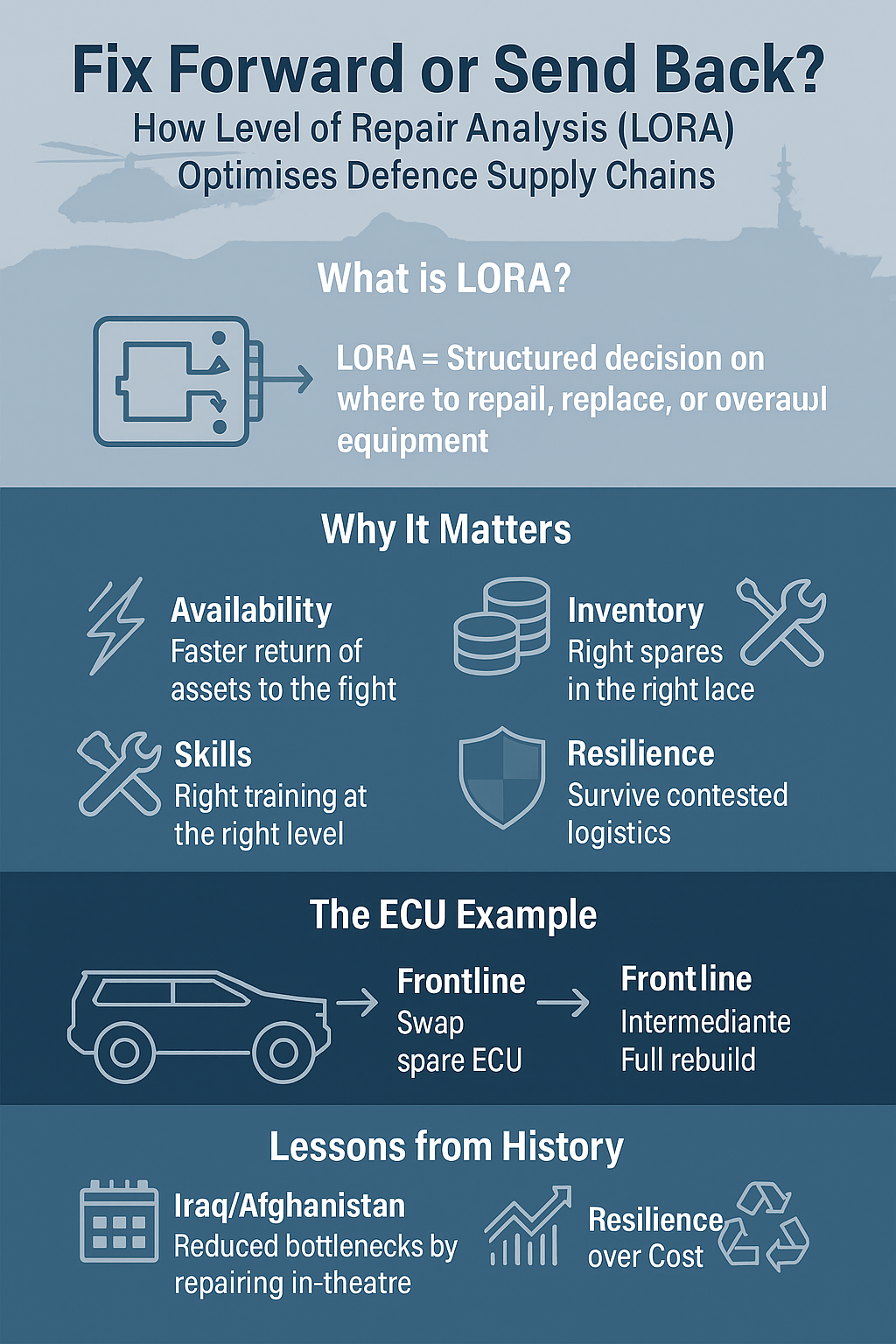

• The workshop throughput rate for vehicle repairs in a deployed theatre.

Each of these has hard limits. Without modelling them, we risk building plans on assumptions rather than evidence.

2. The Tempo of the Fight

UK operations—whether national or NATO-led—run at a tempo dictated by both the adversary and the commander. A critical enabler of that tempo is the supply chain.

Without capacity models that align supply flow with operational tempo, the mission faces risks such as:

• Units being forced to pause for resupply.

• Equipment becoming unavailable due to backlogged maintenance.

• Surge deployments collapsing under logistics strain.

In short: without modelling, Defence risks planning for peace in a time of war.

⸻

Capacity Modelling in NATO Contexts

1. Coalition Complexity

Operating within NATO introduces both opportunity and complexity. While shared logistics agreements and multinational support frameworks can increase resilience, they also complicate assumptions. Each nation contributes different capabilities, follows different logistics doctrine, and has different limitations.

Capacity modelling enables the UK to:

• Understand its own contribution to the wider NATO supply ecosystem.

• Model interoperability gaps, such as fuel standards, container types, or medical evacuation rates.

• Predict bottlenecks caused by shared infrastructure—such as airfields, railheads, or ports of debarkation.

Without modelling, there is a risk that the UK assumes capacity that is, in fact, not available—or overestimates allies’ ability to support at the required scale.

2. The ‘Support to Operations’ Loop

In multinational operations, decision-making is only as good as the support chain underpinning it. If NATO is to act quickly, logistics must not be the rate-limiting factor. The UK must be able to model:

• Pre-positioned stocks and readiness states

• Time to theatre (TTT) across different domains

• Impact of contested logistics (e.g. cyberattacks, denied sea lanes, degraded SATCOM)

Capacity modelling feeds these into the operational planning loop, ensuring that logistics informs, rather than reacts to, mission design.

⸻

Lessons from the Field

1. Exercise Trident Juncture (2018)

During NATO’s largest exercise in recent memory, over 50,000 personnel operated across Scandinavia. The logistics tail was vast: 10,000 vehicles, 250 aircraft, and 65 ships.

While the exercise was a success, it revealed that cross-border logistics coordination, infrastructure limits, and unit movement scheduling were all pain points. Had these been better modelled in advance—particularly the rail and road capacity in Norway—logistical friction could have been reduced.

2. Op Pitting and the Afghan Drawdown (2021)

In a matter of weeks, the UK was forced to execute a large-scale airlift under highly constrained conditions. While Defence planners performed admirably, the crisis exposed the limits of assumption-based planning.

More mature capacity modelling—of airlift capacity, staging areas, and medical capabilities—could have enabled quicker scenario testing and faster mobilisation of alternative plans.

⸻

What Does Effective Capacity Modelling Look Like?

To be effective, capacity modelling must be:

1. Dynamic

Static spreadsheets are no longer enough. Defence needs tools that can run “what-if” scenarios, simulate variable demand, and adjust for real-world disruptions in real-time.

2. Integrated

Capacity models must link across the domains: from fuel pipelines and ammunition stockpiles to movement assets and in-theatre maintenance capabilities. Siloed models create siloed risk.

3. Transparent

Commanders and logisticians must understand model outputs and limitations. If capacity modelling becomes a “black box,” trust breaks down. Clear visualisation, scenario logging, and assumptions tracking are essential.

4. Validated

Models must be grounded in accurate, timely, and complete data—with input from users on the ground. Validation against actual operational outputs ensures the model reflects reality, not aspiration.

⸻

The Role of Digital Engineering and Data Quality

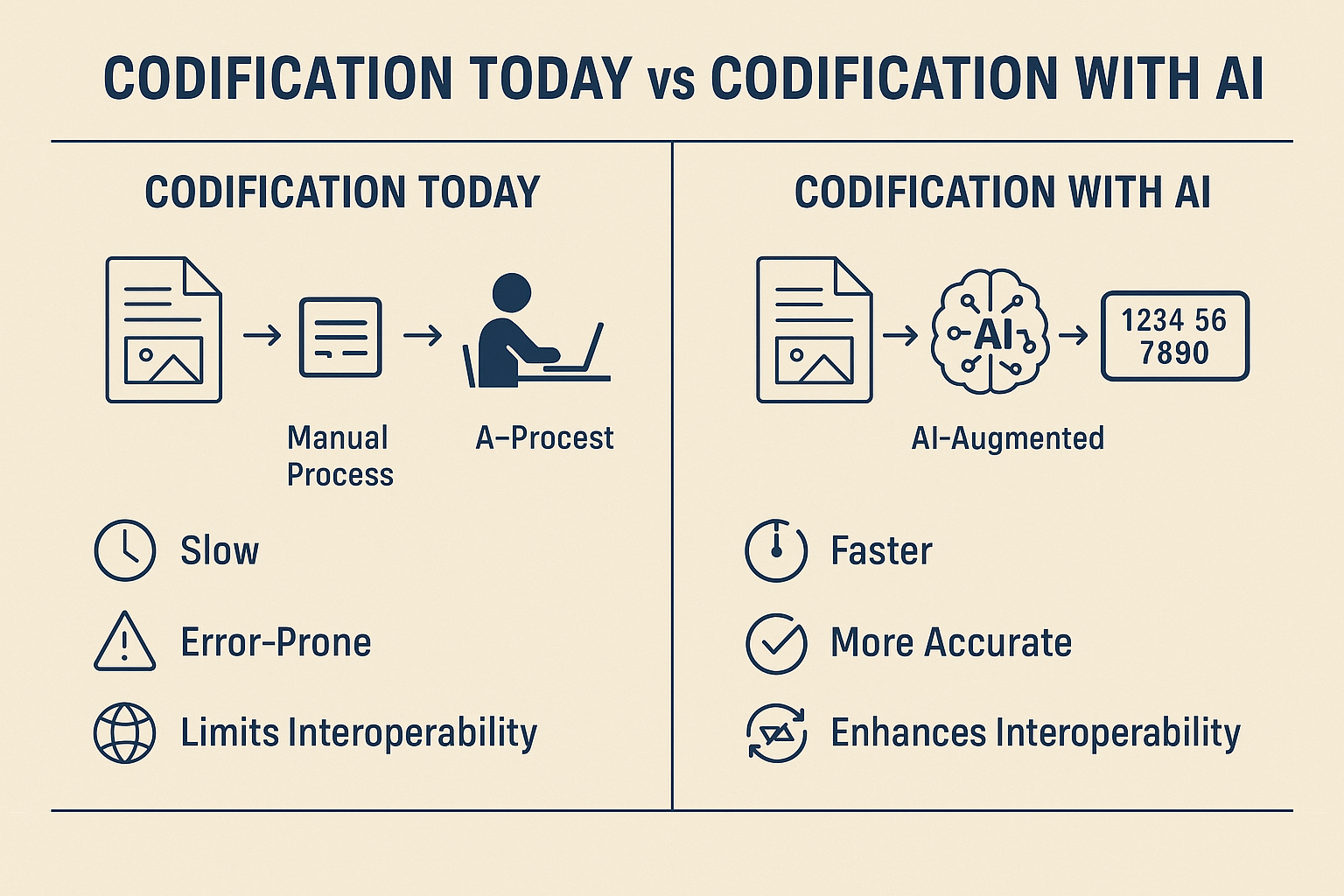

Modern capacity modelling benefits hugely from digital tools—especially digital twins, AI-based forecasting, and simulation software.

However, the utility of these tools is only as good as the data they consume. This is where Defence must redouble efforts:

• Codification must be current and accurate (e.g. NATO Stock Numbers).

• Item-level data (e.g. volumetrics, shelf-life, location) must be maintained.

• Organisational and infrastructure data must be kept live—not treated as once-a-year updates.

Only then can tools like Opus 10, SIMLOX, or military digital twins produce credible outputs.

⸻

Building the UK Defence Capacity Modelling Ecosystem

The Support Operating Model (SOM), DE&S Transformation, and the formation of the Defence Support Digital Backbone all present opportunities to embed capacity modelling into core planning.

To do this, Defence must:

1. Establish Core Modelling Teams

Just as we have core engineering or project control roles, Defence should resource a cadre of logistics capacity modelling professionals—skilled in software, scenario design, and operational context.

2. Train Planners to Use and Challenge Models

Planners must be taught not just to run models, but to challenge them—test assumptions, question inputs, and interpret outputs for commanders.

3. Embed Modelling in Key Processes

Capacity modelling should feature in:

• Deployment planning

• Capability delivery planning

• Defence Exercise design

• Procurement decision-making

It should not be “added on”; it must be built in.

⸻

What’s at Stake if We Don’t Model Capacity?

If capacity modelling is ignored or underutilised, the consequences are predictable:

• Overpromised capability—leading to embarrassment or mission failure.

• Underprepared logistics—leading to lost tempo and force degradation.

• Poor investment decisions—spending on new assets without understanding where the actual bottleneck lies (e.g. buying trucks without increasing storage or loading capacity).

In a NATO context, it could also lead to UK shortfalls impacting coalition credibility, or critical dependencies being overlooked until it’s too late.

⸻

A Call to Action

UK Defence has already made strides in this space, but more must be done. We must:

• Treat logistics capacity modelling as a core function, not an optional exercise.

• Align efforts across domains—land, air, maritime, cyber, and space.

• Share modelling outputs with NATO partners to support joint understanding of capacity limits and opportunities.

As conflict becomes more multi-domain, more dispersed, and more data-driven, our ability to model capacity is now mission critical. We do not get a second chance in war to rethink the warehouse layout, resize the movement plan, or recalibrate the supply flow.

If we want to be ready for what’s next, we must start by modelling what’s possible.

⸻

About the Author

Paul R. Salmon is Chair of the CILT Defence Forum and a Fellow of the Chartered Institute of Logistics and Transport (FCILT), the Institute of Supply Chain Management (FSCM), and the Chartered Management Institute (FCMI). A former RAF engineer turned logistics leader, he champions professionalisation, data-driven decision-making, and modernisation across Defence Support.

Leave a Reply