By Paul R. Salmon, FCILT, FSCM, FCMI

Introduction

When we think about supply chains, we often imagine lorries on motorways, containers stacked in ports, or aircraft delivering pallets into remote bases. In Defence, however, supply chains stretch far beyond these images. They are not only long in terms of miles travelled, but also in the years and decades over which they operate, and in the sheer number of nodes and actors that make them possible.

So, what is the longest defence supply chain in the world? The answer depends on how we measure “long.” Do we mean geographically? Chronologically? Or by sheer organisational complexity? In reality, the Defence enterprise deals with chains that are long in all three dimensions simultaneously.

This article explores the longest defence supply chains through three lenses: distance, time, and complexity.

1. Longest by Distance: From Factory to Foxhole

Distance has always been the most visible measure of military supply chains. The farther forces are deployed from home, the longer the chain must stretch.

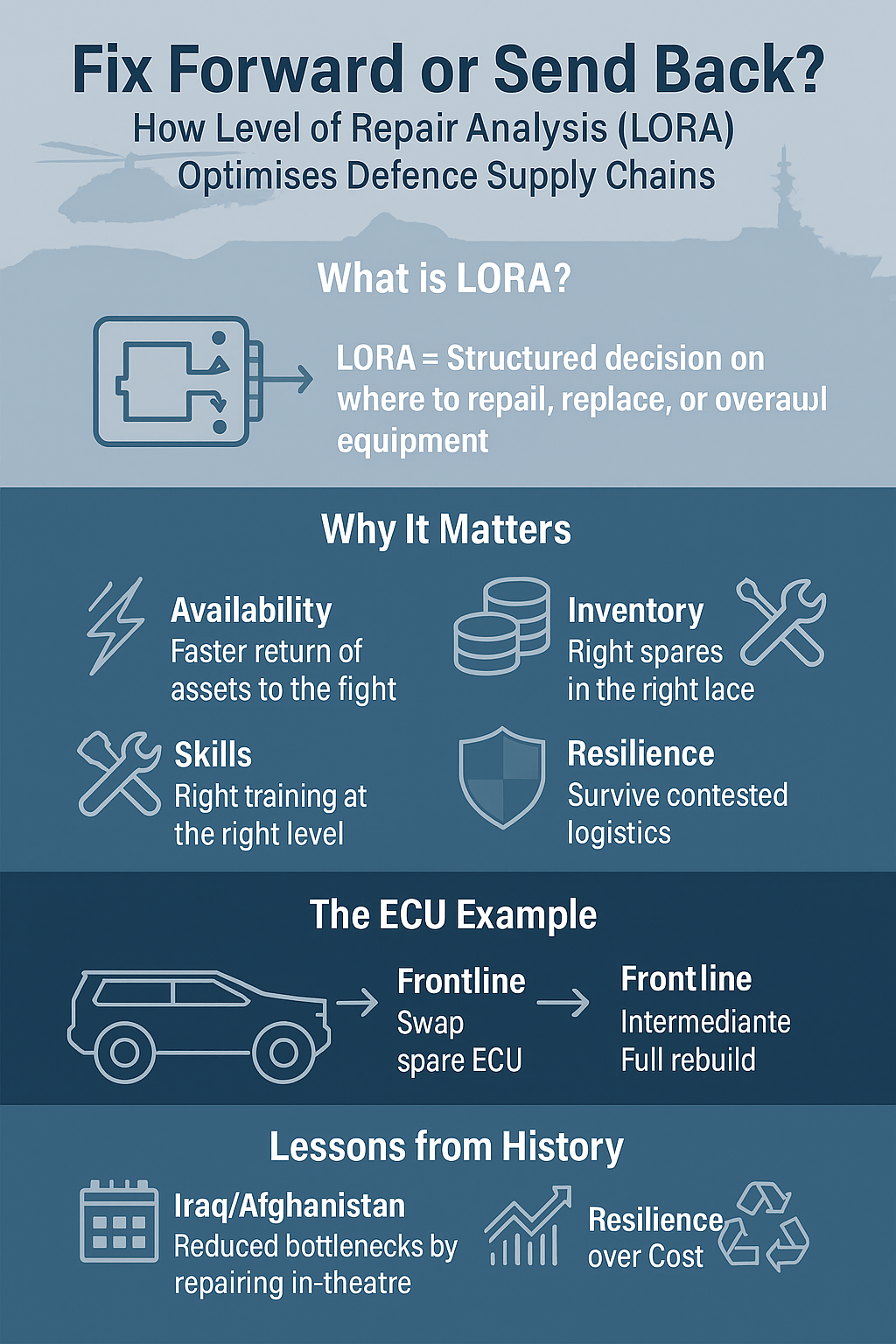

Afghanistan (2001–2014): For NATO and the UK, sustaining operations in Afghanistan was one of the most geographically demanding undertakings in recent history. Supplies often originated in Europe or North America, travelled by sea to ports such as Karachi, Pakistan, and then moved via precarious ground routes through the Khyber Pass or Northern Distribution Network. A simple spare part or ration pack might traverse 7,000 miles before reaching a forward operating base. The Falklands War (1982): For the UK, the Falklands campaign remains a textbook case of distance-driven logistics. Every litre of fuel, every round of ammunition, and every loaf of bread had to cross 8,000 miles of ocean from the UK to the South Atlantic. The Royal Fleet Auxiliary and merchant shipping pressed into service (the “Ships Taken Up From Trade”) became the backbone of a supply chain stretched to its physical limits. Ukraine (2022–present): Today, the resupply of Ukraine highlights another dimension of distance. While Europe is geographically closer than Afghanistan or the South Atlantic, the routes are strategically longer because they involve navigating political restrictions, avoiding interdiction, and coordinating across multiple allied nations. The supply lines stretch not only across land borders but also across the global defence industrial base producing ammunition, drones, and spare parts.

2. Longest by Time: The Century-Long Lifecycle

The second way to define length is time. Defence supply chains often begin not at the point of deployment but decades earlier — in research and design — and continue decades after retirement, through dismantling and disposal.

Nuclear Submarines: From uranium mining and reactor development, through decades of at-sea service, to eventual decommissioning and disposal of nuclear material, the supply chain of a submarine stretches over nearly a century. The UK’s Astute-class boats, for example, involve supply lines that began in the 1990s, will sustain the fleet until the 2040s, and will require safe dismantling well into the second half of the 21st century. Few supply chains in the world carry such a temporal burden. Fast Jets (Typhoon, F-35): The Eurofighter Typhoon’s lineage stretches from design studies in the 1980s, through production in the 1990s and 2000s, and continuing sustainment into the 2040s. That’s a 60-year supply chain. The F-35 Joint Strike Fighter will be even longer: design began in the 1990s, full service life is planned to at least 2070, giving the programme a 75-year through-life chain. Ordnance and Ammunition: Even items that seem consumable can span decades. Ammunition stockpiles created during the Cold War are still being used today in Ukraine. This means some “supply chains” for artillery shells began on factory floors in the 1970s and 1980s, only reaching their point of use nearly 50 years later.

3. Longest by Complexity: The Global Web

The third and perhaps most fascinating definition of length is complexity. Some chains may not be the furthest or the longest-lasting, but the sheer number of hands a part passes through makes them labyrinthine.

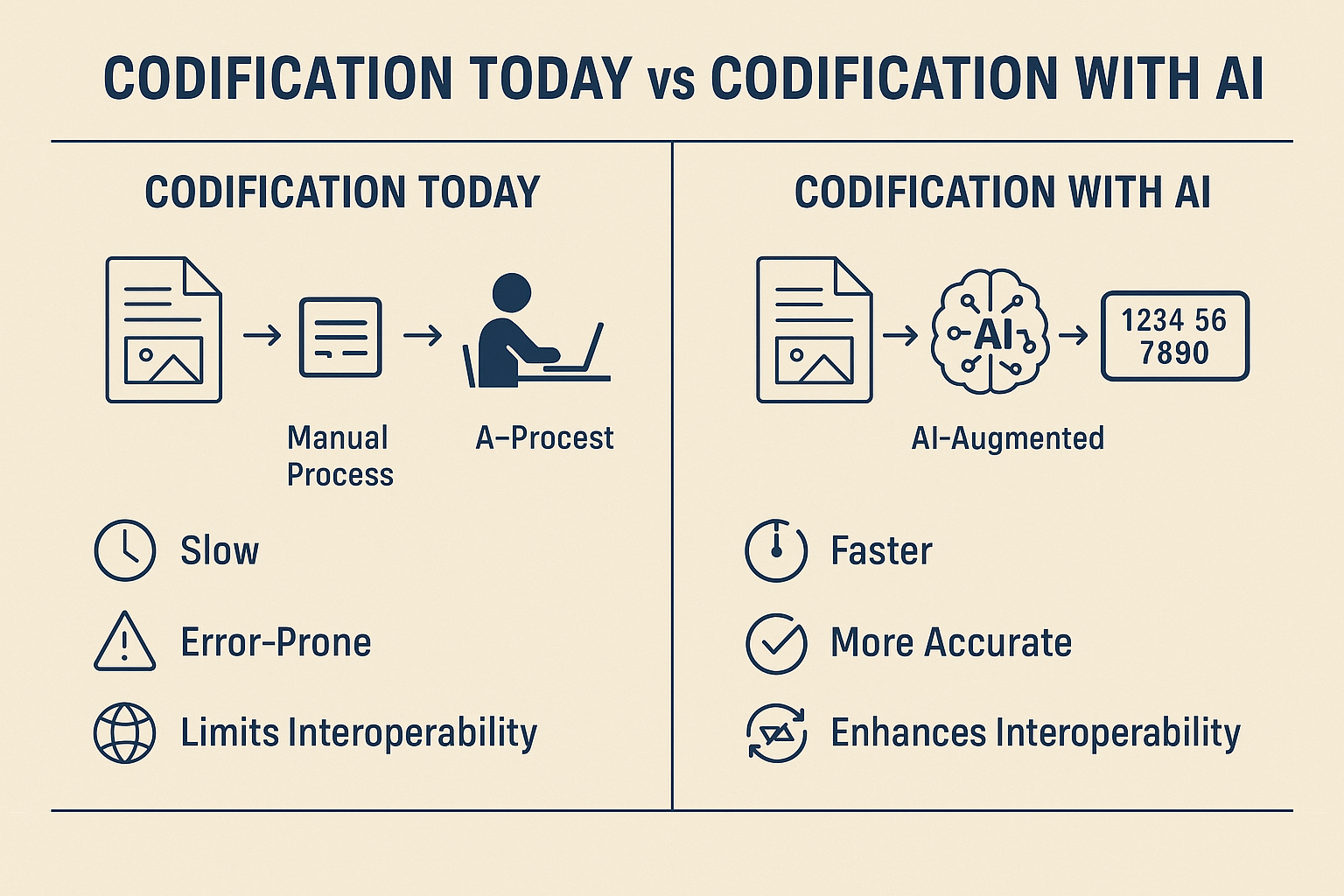

F-35 Joint Strike Fighter: With over 1,500 suppliers in 45 US states and nine partner nations, the F-35 supply chain is arguably the most complex military production and sustainment network ever assembled. A single fighter involves parts manufactured in the UK, software written in the US, composites from Italy, and avionics from Japan — all converging into one aircraft. The chain is long not because of miles but because of the sheer number of interdependent steps. Globalised Defence Industry: Modern supply chains are deliberately designed to be multinational. Ships built in South Korea, fitted with UK weapons, sustained with US radar parts and European electronics, illustrate how length is no longer just linear but networked. This complexity makes chains long in ways that are hard to map, let alone manage.

4. When Long Becomes a Liability

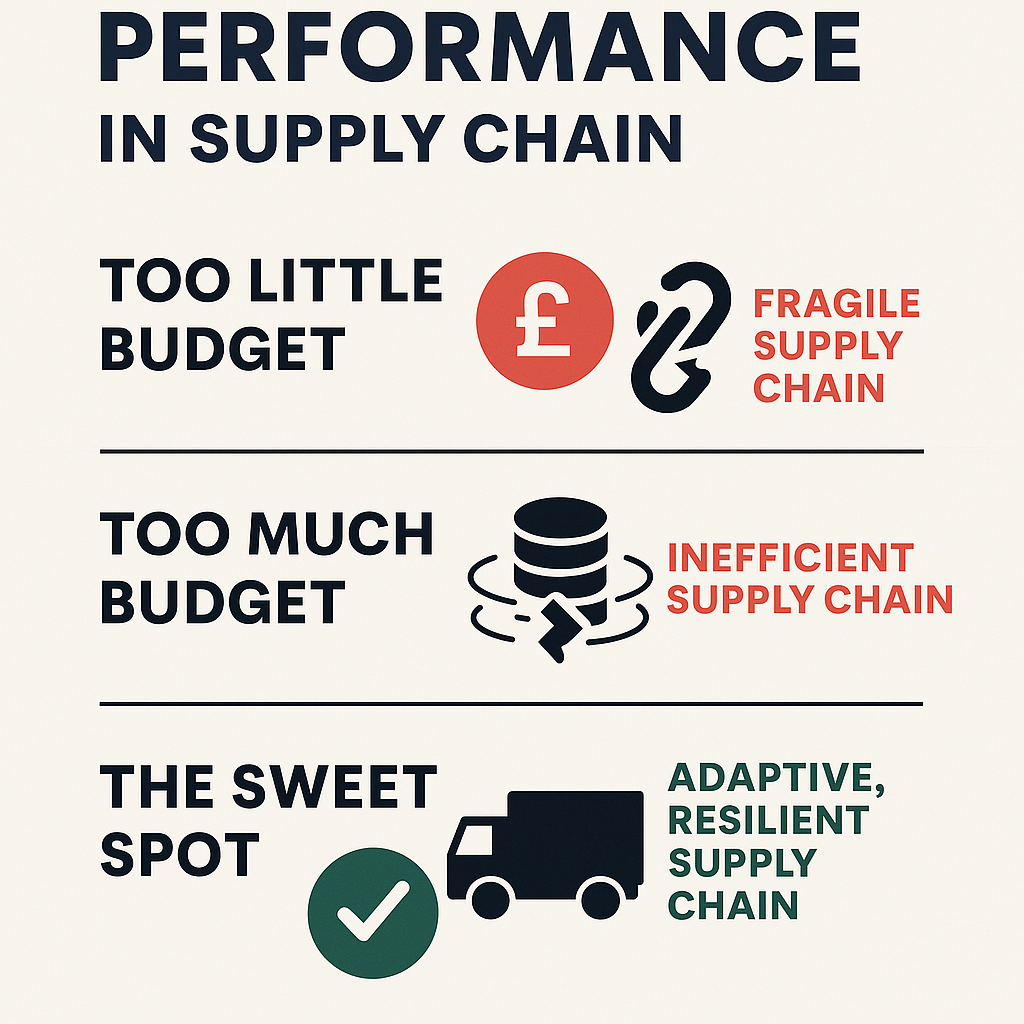

Long supply chains, in all senses, introduce risk. The longer the distance, the more chance of interdiction. The longer the time, the more vulnerable to obsolescence. The more complex the structure, the greater the exposure to disruption or political tension.

In Afghanistan, convoys stretching across Pakistan became frequent targets. In submarine disposal, delays leave the UK still storing retired nuclear boats in Devonport and Rosyth decades after decommissioning. In globalised programmes like F-35, a single supplier outage in one nation can ground fleets worldwide.

Length is not just a measure of endurance but of vulnerability.

5. Lessons for Today and Tomorrow

The study of the longest defence supply chains offers some clear lessons:

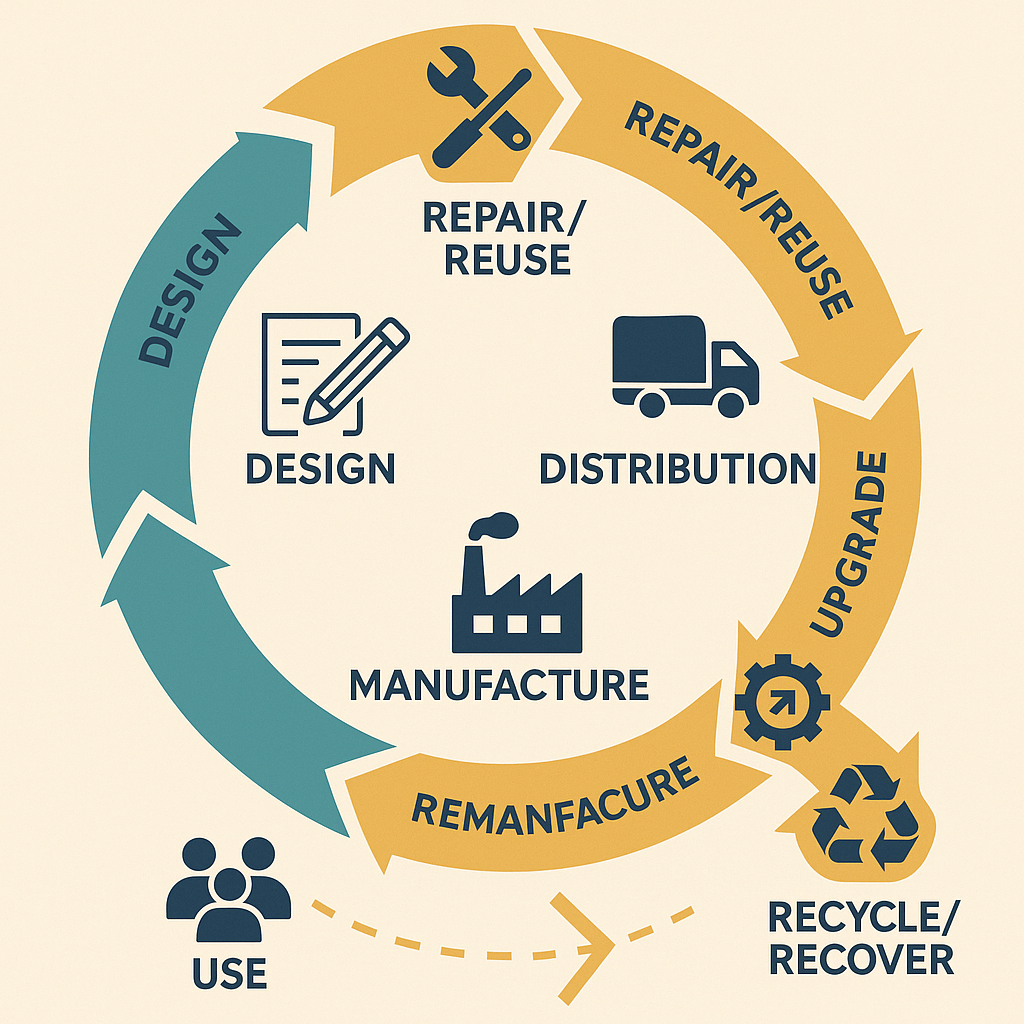

Redundancy and diversification are essential. Long-distance chains must have multiple routes, whether through allied ports, overland alternatives, or prepositioned stock. Lifecycle planning must extend from design to disposal. Defence cannot afford to treat sustainment and dismantling as afterthoughts. Resilience must be engineered in. Complexity is inevitable, but transparency, data sharing, and digital twins can allow Defence to manage global webs with confidence. Shorter isn’t always possible — but smarter always is. Sometimes the longest chains are unavoidable. But by modelling risks, collaborating with industry, and leveraging new technologies like additive manufacturing, Defence can shorten or “collapse” parts of the chain.

Conclusion

So, what is the longest defence supply chain in the world? The answer is: there isn’t just one. It is a matter of perspective.

By distance, the Falklands or Afghanistan stand out. By time, the nuclear submarine or fast-jet programmes stretch across generations. By complexity, the F-35 sets the benchmark.

The truth is that Defence lives with supply chains that are longer, in every sense, than almost any civilian enterprise. They span continents, generations, and thousands of suppliers. And as global threats evolve, the challenge is not simply to maintain these chains, but to make them resilient, adaptive, and fit for the contested world of tomorrow.

In Defence, the longest supply chain is the one that never

Leave a Reply