By Paul R Salmon, FCILT, FSCM, FCMI

Introduction

For decades, global supply chains have been managed on a linear model: take, make, use, dispose. Raw materials are extracted, turned into products, consumed, and ultimately discarded. This model has delivered efficiency, scale, and economic growth — but it has also created vulnerability. Rising material scarcity, supply shocks, environmental regulations, and geopolitical contestation now expose the fragility of linear supply chains.

Enter supply chain circulation. Rooted in circular economy principles, it is the idea that materials, products, and value should flow in loops, not straight lines. Circulation means keeping resources in play for as long as possible — through reuse, repair, remanufacture, and recycling — to reduce dependency, increase resilience, and unlock new forms of value.

In 2025, circulation is no longer an environmental “nice to have.” It is a strategic necessity for organisations, governments, and Defence alike.

The Circulation Concept

At its core, supply chain circulation is about designing out waste and ensuring that every product and component has multiple lives. Instead of a one-way flow from factory to landfill, circulation embeds reverse logistics loops that bring materials back for another round of use.

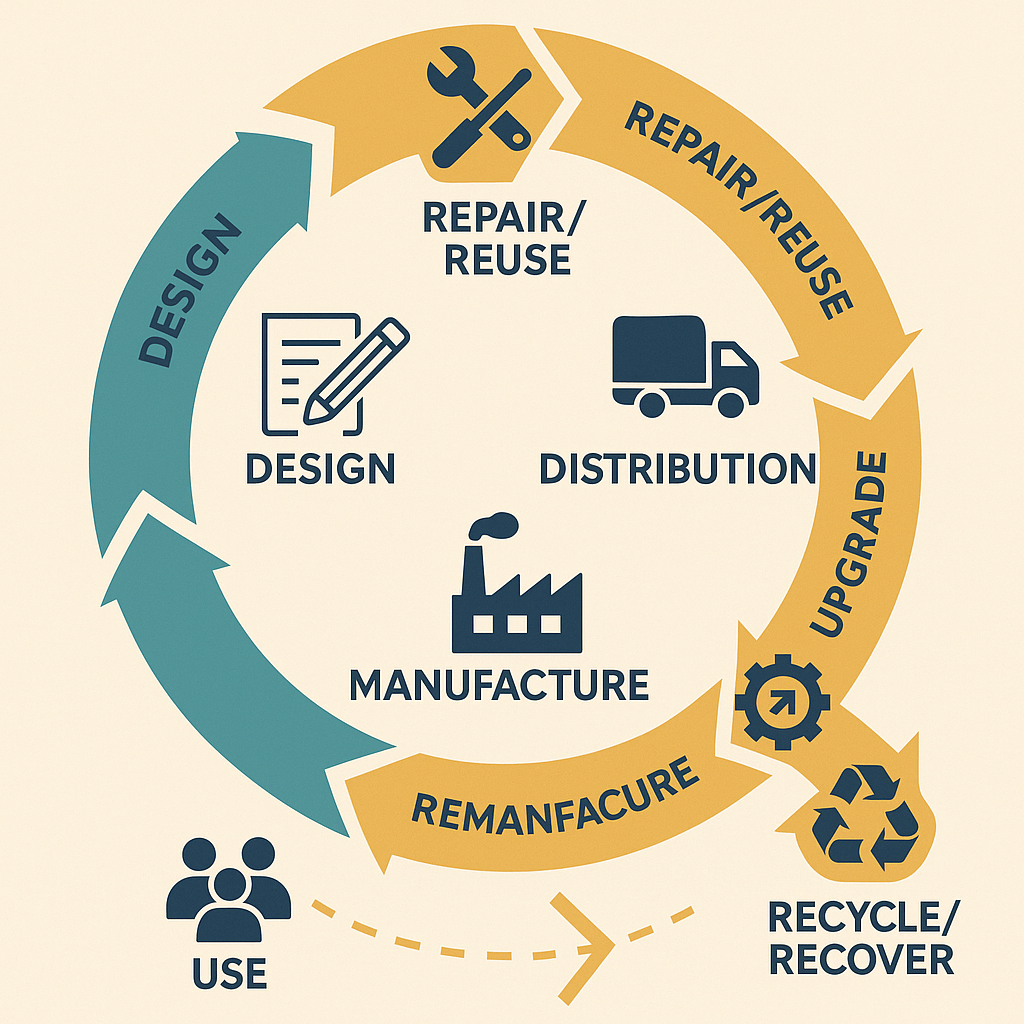

These loops can take several forms:

Reuse: Re-deploying assets directly, with minimal intervention (e.g., NATO pooled inventories). Repair: Extending product lifespans through maintenance or part replacement. Remanufacture: Returning used products to “as new” condition, often with performance upgrades. Recycle: Recovering raw materials for re-entry into production cycles.

Every loop captures value that would otherwise be lost — whether that’s operational availability, financial savings, or environmental benefit.

Business Models That Enable Circulation

Circulation doesn’t happen by accident; it requires new business and contracting models:

Product-as-a-Service (PaaS): Instead of owning equipment outright, customers pay for outcomes. Rolls-Royce’s “power by the hour” jet engine support model is a leading example. Take-Back Schemes: OEMs design responsibility for end-of-life recovery into contracts, ensuring components are remanufactured or recycled. Sharing & Pooling Platforms: Multiple users share access to high-value assets, improving utilisation and minimising duplication. Pay-per-Use: Equipment is billed by usage, incentivising suppliers to maximise product life and reuse.

These models align incentives — suppliers gain from keeping assets in circulation, and customers gain from availability without full ownership costs.

Circulation in Defence Supply Chains

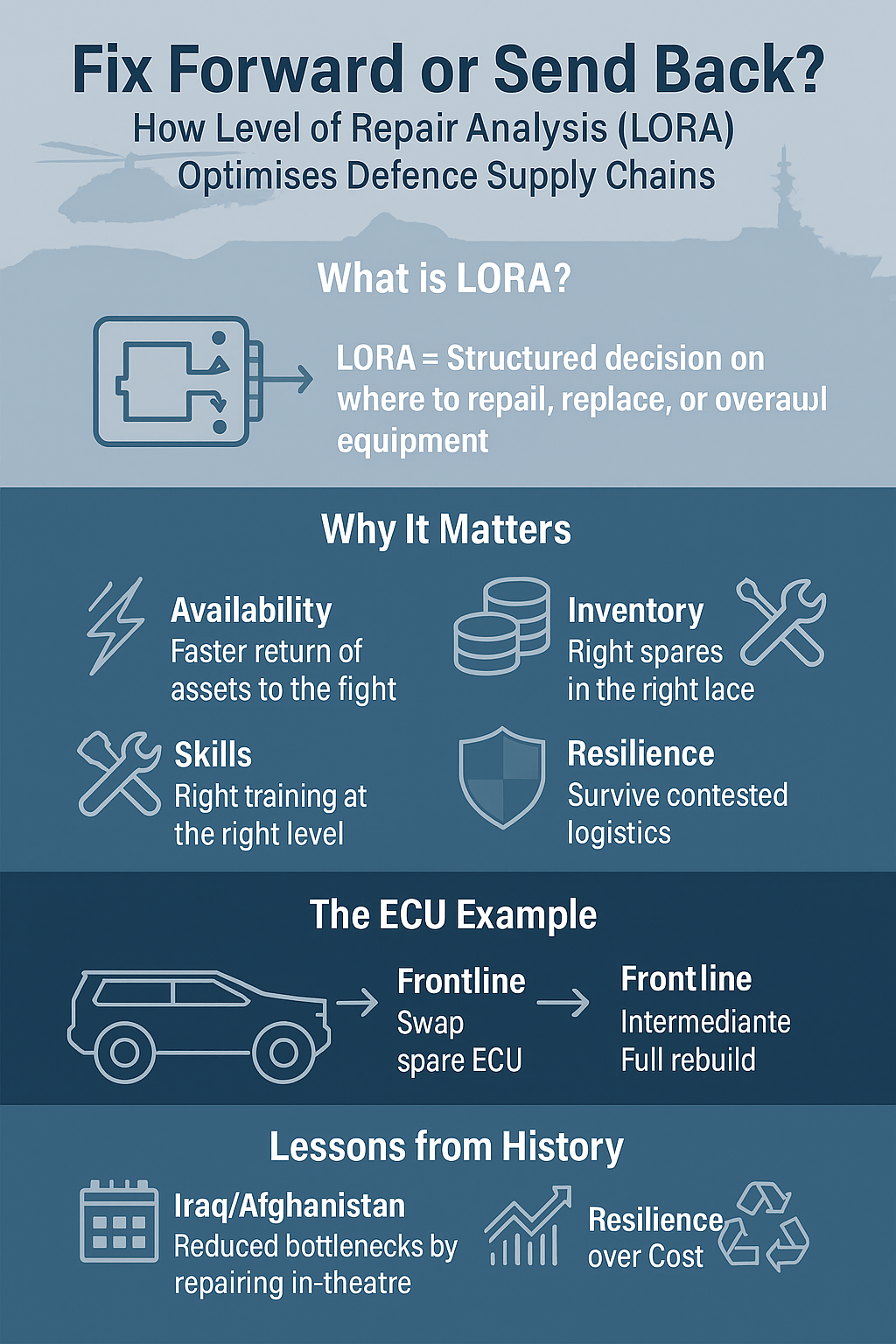

Defence supply chains are uniquely positioned to benefit from circulation. Budgets are tight, operational theatres are complex, and equipment often has life cycles spanning decades. Circular practices already exist in pockets but need to be systematised.

Examples include:

Cannibalisation & Part Harvesting: Components are recovered from retired platforms and reused to sustain in-service fleets. 3D Printing at the Front Line: Additive manufacturing produces spares in-theatre, reducing reliance on extended resupply chains. NATO Shared Stocks: Circulation across allied forces reduces duplication and ensures resilience in contested environments. Upgrade over Replace: Extending the service life of vehicles, ships, and aircraft with modular, upgradable components. Circular Packaging & Fuels: Reusable containers, biodegradable pallets, and synthetic fuels create logistics loops that reduce resupply burden.

Defence’s through-life capability management (TLCM) philosophy is, in many ways, a military version of circulation. It recognises that assets should be designed, supported, and adapted for maximum longevity and value.

Lessons from the Civilian World

The private sector has already demonstrated the business case for circulation:

Caterpillar: Runs one of the world’s largest remanufacturing networks, stripping down and rebuilding engines and heavy equipment to “like-new” standard. Apple: Its “Daisy” robot dismantles iPhones, recovering rare earth metals for reuse in new devices. IKEA: Offers furniture take-back schemes and resale programmes to extend product lifespans. H&M: Runs global clothing recycling bins to feed old textiles into new production loops.

These cases prove circulation isn’t just green policy — it’s commercially viable, cost-effective, and reputation-enhancing.

Benefits of Circulation

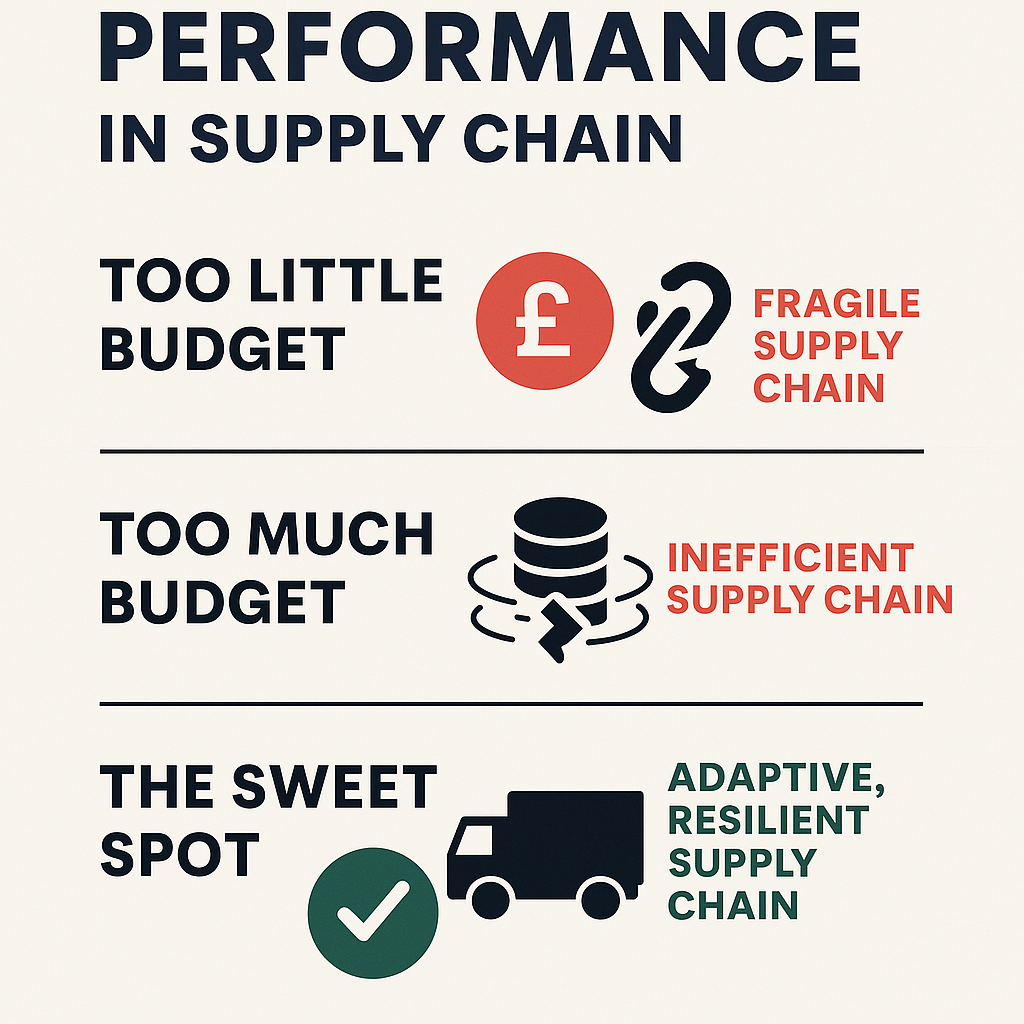

The advantages of adopting circulation models in supply chains are wide-ranging:

Resilience: Diversifies sources of supply, reducing reliance on vulnerable global supply chains. Cost Efficiency: Reduces procurement and disposal costs while maximising the value of existing assets. Sustainability: Cuts emissions, reduces waste, and aligns organisations with Net Zero ambitions. Operational Readiness: In Defence, ensures that equipment remains available, serviceable, and deployable in austere or contested environments. Innovation & Reputation: Positions organisations as leaders in sustainable logistics.

Challenges and Enablers

Shifting to circulation is not without difficulty.

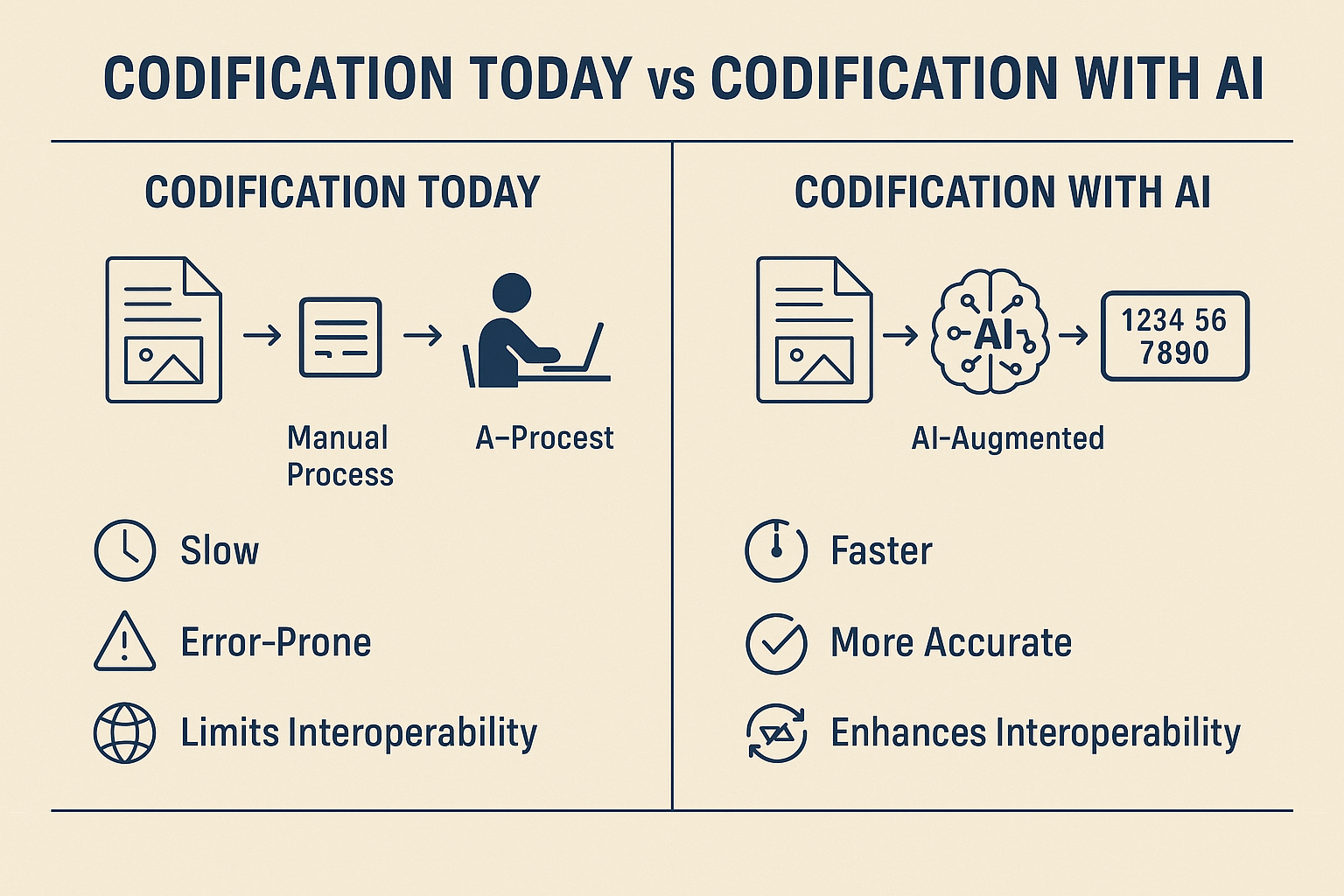

Technical Certification: In Defence and aerospace, reused or remanufactured parts must meet strict airworthiness and safety standards. Supply Chain Complexity: Integrating reverse logistics into global supply chains adds new layers of coordination. Cultural Barriers: “New is better” mindsets persist among customers, operators, and engineers. Digital Visibility: Circulation depends on data — tracking asset condition, provenance, and lifecycle performance requires investment in IoT, blockchain, and digital twins. Contracting & Incentives: Procurement rules must evolve to favour circular models over linear purchasing.

Enablers include clear policy frameworks, cross-sector partnerships, digital innovation, and education to build trust in circular models.

The Future of Supply Chain Circulation

Looking ahead, supply chain circulation will be driven by:

AI & Predictive Analytics: Forecasting component failures and optimising repair/reuse loops. Additive Manufacturing Networks: Printing spares closer to point of use. Digital Product Passports: Embedded data on provenance, materials, and maintenance history. Cross-Border Circularity: NATO and EU collaboration to create shared circular supply ecosystems. Defence-Industry Collaboration: Joint frameworks that bring military and civilian logistics into a common circular model.

The UK has the opportunity to lead, combining its Defence Support Strategy with its Net Zero ambitions to make circulation a hallmark of future supply chain design.

Conclusion

Circulation is more than sustainability branding. It is a new operating logic for supply chains — one that sees materials, products, and value continuously recaptured, rather than wasted.

For Defence, it offers resilience under pressure, availability in contested logistics, and cost-effectiveness across decades of asset life. For industry, it offers competitive advantage and alignment with ESG imperatives.

The future of supply chains will not be linear. It will be circular — and circulation will be the defining feature of how organisations secure value, readiness, and sustainability in the decades ahead.