Author: Paul R Salmon FCILT, FSCM, FCMI

This paper explores the counterfactual: what happens if the UK Defence supply chain does not adopt a globalised approach, or chooses to confine itself to NATO-only partnerships? While globalisation brings risks, rejecting it outright or narrowing collaboration would carry heavier costs—industrial overstretch, reduced innovation, interoperability challenges, and strategic marginalisation. The paper outlines the consequences of these two alternative approaches, considers the trade-offs, and concludes that a balanced global outlook is essential for UK Defence resilience and credibility.

1. Introduction

Much analysis of Defence supply chains focuses on the benefits and risks of globalisation. Yet the more revealing question may be: what happens if the UK does not go global?

Two counterfactuals are worth considering:

A UK-only supply chain model—domestically anchored, isolated from broader global networks. A NATO-only model—confined to transatlantic and European partners, excluding wider global partnerships.

Both scenarios highlight the importance of global integration not simply as a choice, but as a necessity for the UK’s Defence and security posture.

2. Scenario 1: Rejecting Globalisation – The UK-Only Model

A purely domestic Defence supply chain may appear attractive in terms of sovereignty, control, and resilience. However, the UK faces several structural limitations that make self-sufficiency in Defence procurement unrealistic.

2.1 Industrial Overstretch

The UK no longer has the industrial depth to produce all critical defence technologies, from advanced semiconductors to rare earth minerals. Attempting to re-nationalise production would stretch limited resources, creating bottlenecks and inflating costs.

2.2 Innovation Deficit

The pace of military innovation is increasingly global and dual-use. Technologies such as AI, quantum sensing, and autonomous platforms are emerging from global ecosystems involving academia, start-ups, and non-traditional suppliers. A UK-only approach risks cutting itself off from this flow of innovation.

2.3 Reduced Interoperability

UK Armed Forces rely on interoperability with allies in coalition operations. A nationally isolated supply chain would produce platforms, spares, and standards that diverge from NATO and allied forces, creating friction in joint deployments.

2.4 Economic Burden

Without multinational cost-sharing, the unit cost of platforms would increase significantly. For example, the F-35 programme’s affordability depends on pooled R&D across partner nations. An isolated UK would face fewer aircraft for higher outlay.

2.5 Strategic Irrelevance

By turning inward, the UK would risk becoming less relevant to allies. A Defence force that cannot interoperate effectively or share in industrial programmes may be seen as a less valuable coalition partner.

3. Scenario 2: Limiting to NATO-Only Partnerships

A NATO-only Defence supply chain model avoids the isolation of the UK-only approach, but brings its own risks.

3.1 Over-Reliance on the US

In practice, NATO-only partnerships often mean dependence on the US Defence industrial base. While US technology is world-leading, export controls (e.g., ITAR restrictions) can constrain UK autonomy in using or upgrading systems.

3.2 Missed Industrial Opportunities

Important technological advances are being made outside NATO—particularly in the Indo-Pacific (e.g., Japan, South Korea, Australia). Restricting partnerships to NATO excludes the UK from tapping into these ecosystems.

3.3 Regional Concentration of Risk

A NATO-only supply chain is heavily Euro-Atlantic centric. This regional concentration creates shared vulnerabilities—e.g., to European energy crises or disruption in North Atlantic logistics routes.

3.4 Strategic Blind Spot in the Indo-Pacific

The UK’s Integrated Review commits to a tilt towards the Indo-Pacific. Yet a NATO-only supply chain framework constrains the UK’s ability to build Defence industrial links with Indo-Pacific democracies (e.g., through AUKUS, FPDA), weakening credibility in that region.

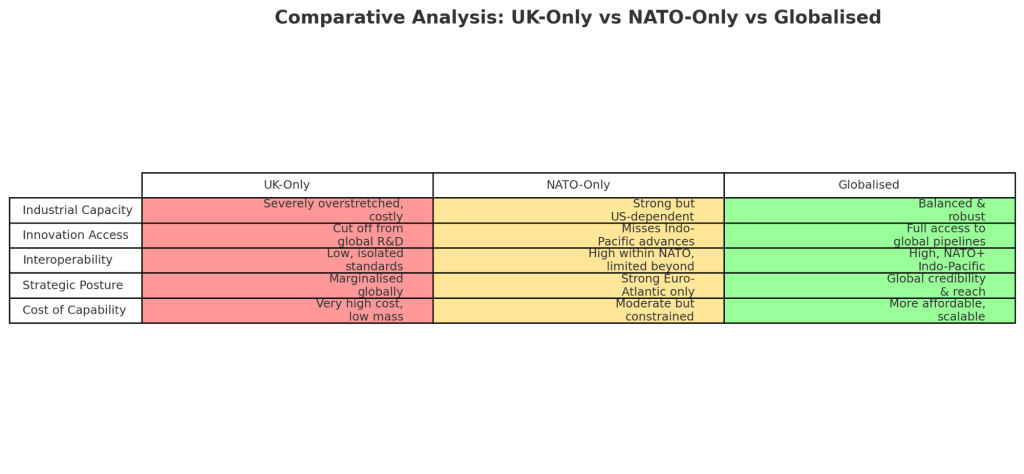

4. Comparative Analysis: UK-Only vs NATO-Only

5. The Strategic Cost of Non-Globalisation

5.1 Loss of Agility

In contested logistics, agility requires diverse supply routes and sources. Narrowing to domestic or NATO-only erodes flexibility.

Case Study: Suez Canal Disruption

When the Ever Given blocked the Suez Canal in 2021, supply chains globally were affected. A UK-only or NATO-only sourcing model would have had no access to alternative Asia-Pacific routes or suppliers, compounding disruption.

5.2 Weakening of Alliances

Insularity sends a political signal. UK credibility rests on being globally engaged; narrowing supply chains risks reputational harm and diminished influence.

5.3 Technological Backwardness

Falling even a generation behind in military technology is decisive. A restricted model risks technological obsolescence.

5.4 Economic Inefficiency

Both non-global models raise costs, reducing the affordability of a balanced, resilient force structure.

6. Policy Implications

Rejecting globalisation or adopting NATO-only is not viable. The UK must:

Anchor in NATO while extending industrial and supply chain links to Indo-Pacific democracies and trusted global partners. Protect sovereign capabilities in key strategic domains (nuclear, cryptography, parts of aerospace). Diversify supply bases to spread risk across geographies. Invest in transparency tools (e.g., supply chain mapping, ChainCheck) to identify dependencies early.

7. Conclusion

Non-globalisation is not simply an alternative—it is a strategic dead end.

A UK-only model is unaffordable, technologically backward, and strategically isolating. A NATO-only model preserves Euro-Atlantic strength but risks global irrelevance and over-dependence on the US.

Globalisation—anchored in NATO, extended to Indo-Pacific partners, and reinforced by selective sovereign capabilities—remains the only viable pathway.