By Paul R Salmon FCILT FSCM

In the world of supply chain and logistics, few moments are as critical as the introduction of a new fleet – whether it’s a commercial airline bringing in the next generation of fuel-efficient aircraft, a defence organisation fielding a new class of armoured vehicles, or a logistics operator adopting a fleet of electric delivery vans.

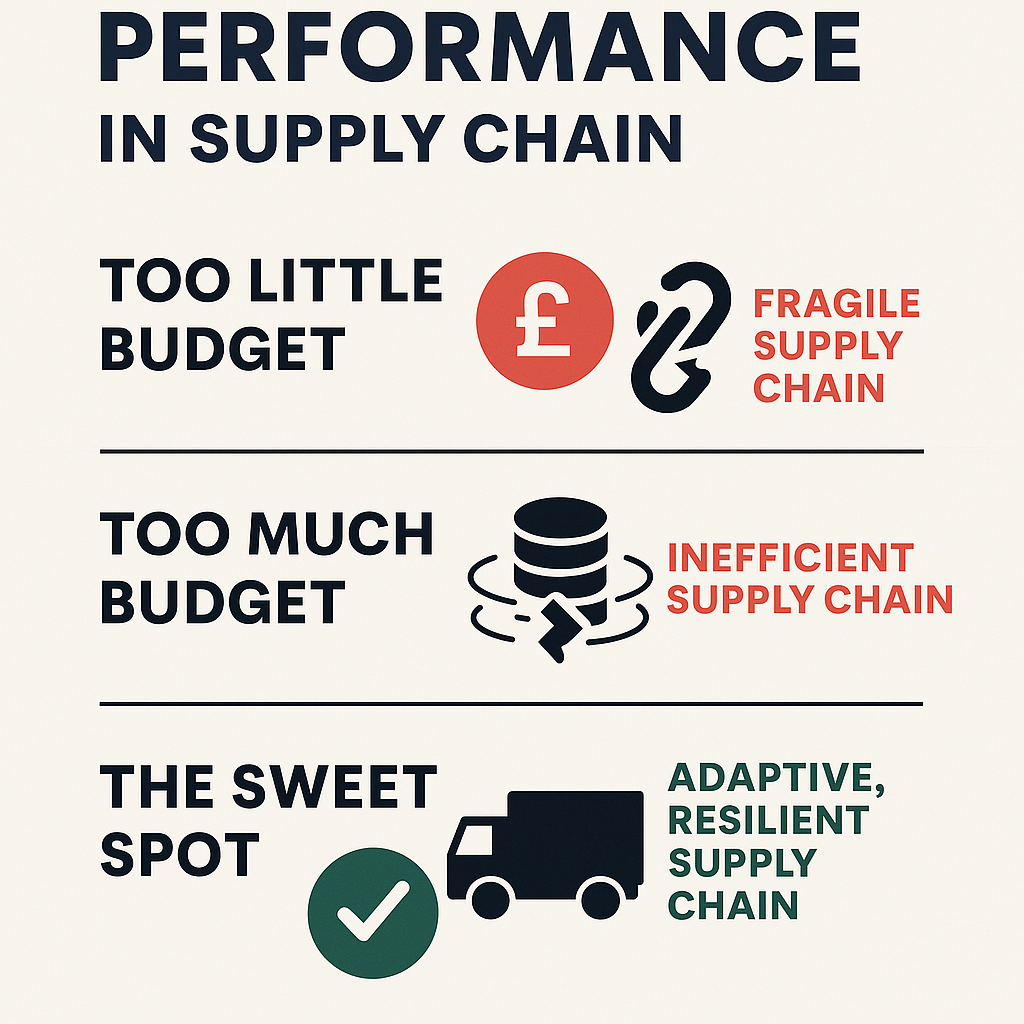

The instinct to “get it right first time” often drives procurement teams towards buying all the inventory up front, in the belief that doing so will safeguard operational readiness and avoid embarrassing supply shortages. But in reality, this approach can create as many problems as it solves – tying up capital, creating obsolescence, and locking organisations into sparing strategies that quickly become outdated.

Instead, modern supply chain leaders are turning to phased, data-driven fleet build-up strategies, which focus on buying the right parts, at the right time, in response to real-world data and evolving requirements. This article explores why this shift is necessary, how it works in practice, and what civilian and military organisations can learn from each other.

The Traditional Approach: Buy Big, Buy Early

When a new fleet enters service, the pressure on supply chain and logistics teams is intense:

What if parts aren’t available when the first failures occur? What if operational commanders or customers complain about lack of availability? What if suppliers can’t deliver later due to lead times or production changes?

To mitigate these risks, many organisations pursue a “buy big, buy early” approach. They:

✅ Procure a comprehensive set of spares up front, based on engineering predictions and provisioning models.

✅ Frontload the supply chain with stock to avoid immediate shortages.

✅ Assume the initial sparing model will remain valid throughout the fleet’s early life.

At first glance, this seems prudent. However, in practice, it often leads to:

Overstocking: Parts with predicted high failure rates turn out to be ultra-reliable. Obsolescence: Components are superseded, modified, or redesigned before the original stock is even used. Tied-up Capital: Millions (or even billions) in cash are locked into warehouse shelves, unavailable for other priorities.

A striking example comes from the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter programme, where initial spares packages were procured years in advance – only to require massive reconfiguration as real-world usage revealed different failure patterns and higher-than-expected repair times.

A Better Way: Phased, Data-Driven Build-Up

Modern supply chain practice advocates for a progressive inventory build-up strategy. The principles are simple:

Start Small, Start Smart Focus initial provisioning on high-priority, high-risk items where failure will directly impact availability. Use early reliability data and engineering analysis to refine the list. Use Real-World Data As the fleet enters service, capture actual usage, failure, and maintenance data to refine sparing assumptions. Adjust procurement plans based on updated Mean Time Between Failures (MTBF) and supply chain performance. Scale Up Dynamically Expand inventory holdings as necessary, but only in response to clear demand signals. Leverage supplier flexibility and agile contracting to avoid overcommitment.

This approach aligns with lean inventory principles, focusing on just-in-time and just-enough provisioning without sacrificing readiness.

Civilian Example: Airlines and Initial Provisioning

In the commercial aviation world, airlines introducing new aircraft face similar dilemmas.

When Boeing launched the 787 Dreamliner, some early operators opted for extensive spares packages to mitigate supply chain risk. Others, however, worked closely with Boeing’s GoldCare programme, which provides “power by the hour” support and progressive sparing.

The latter approach allowed airlines to:

✈️ Avoid stocking parts that ultimately demonstrated high reliability.

✈️ Access spares pools rather than holding all inventory in-house.

✈️ Free up capital for other investments, such as route expansion and cabin upgrades.

Today, many airlines favour consumable and rotatable spares pools and rely on OEMs to manage inventory risk, reducing the temptation to buy everything up front.

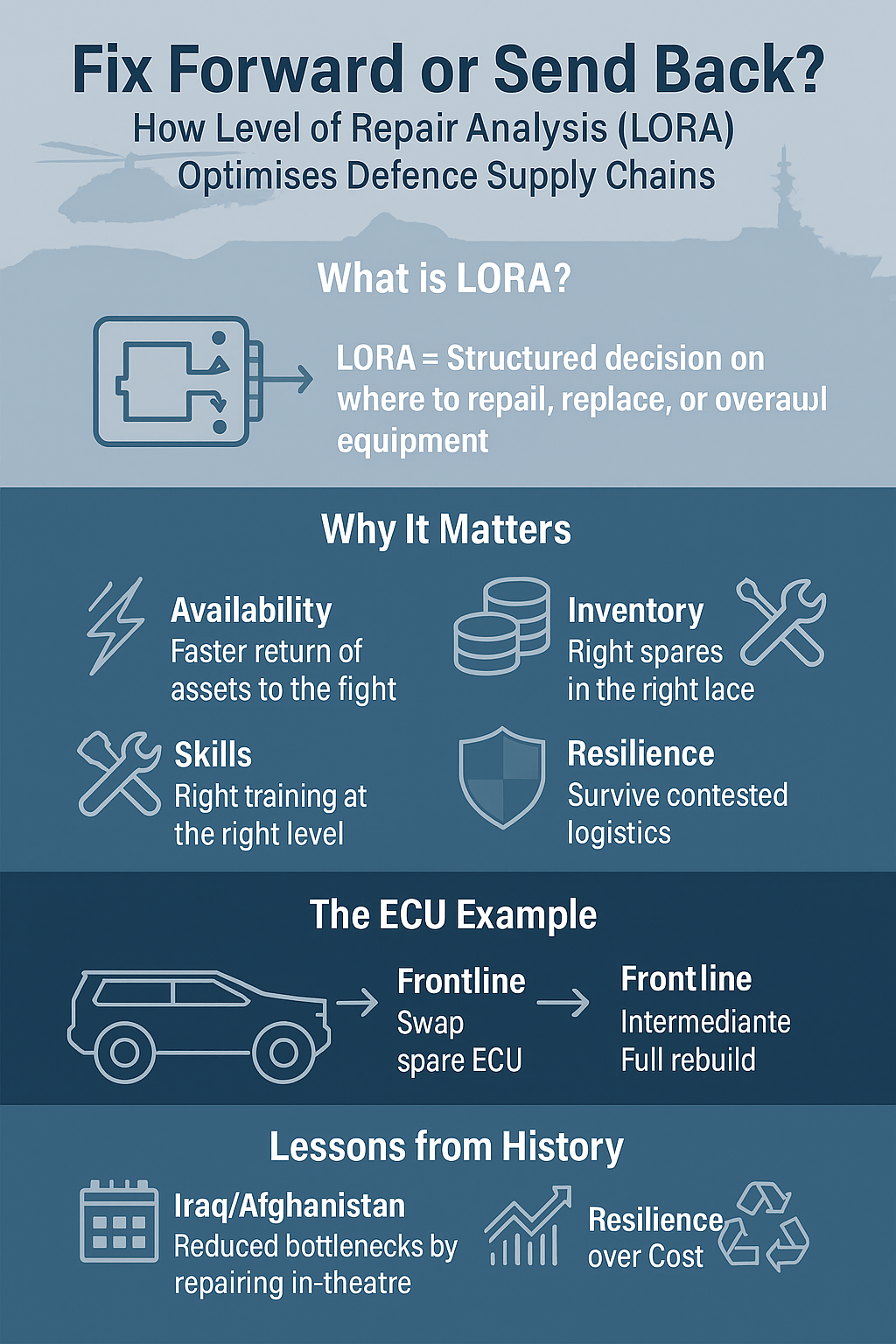

Defence Example: Armoured Vehicle Programmes

In defence, the stakes are often higher. When the UK Ministry of Defence introduced the Foxhound Light Protected Patrol Vehicle, initial sparing assumptions were based on laboratory testing and limited field trials.

However, operational experience in Afghanistan revealed different failure modes due to harsh terrain and intense usage cycles.

Had the MOD purchased all predicted spares up front, it would have risked:

Stocking parts that never failed. Facing shortages of parts that failed unexpectedly. Wasting valuable funds in a highly constrained defence budget.

Instead, the MOD adopted a phased approach, working with suppliers to adjust provisioning plans and introduce modifications to improve reliability.

Benefits of a Phased Approach

✅ Financial Flexibility

Avoid tying up capital in parts you may never use. Redirect funds to fleet upgrades, training, or supply chain resilience.

✅ Reduced Obsolescence

Minimise the risk of holding stock for components that are redesigned or improved.

✅ Better Alignment with Reality

Base sparing decisions on actual usage, not theoretical predictions.

✅ Increased Supplier Collaboration

Foster partnerships with OEMs and third-party providers to manage risk dynamically.

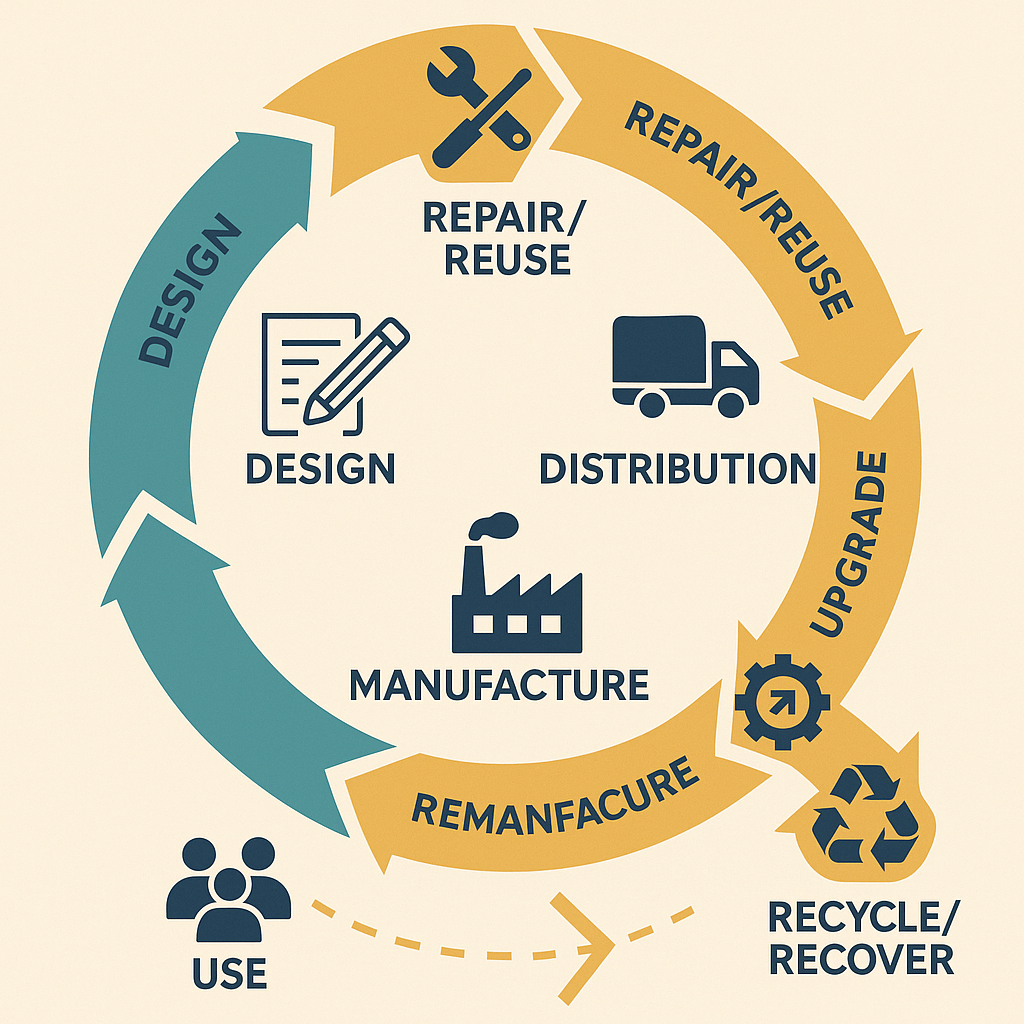

✅ Improved Sustainability

Reduce waste by only procuring what is needed, when it is needed.

Challenges and Considerations

Of course, a phased build-up is not without risks:

⚠️ Supplier Lead Times

Long production cycles for critical parts can make reactive buying difficult. Mitigation: Use flexible contracts and supplier development to improve responsiveness.

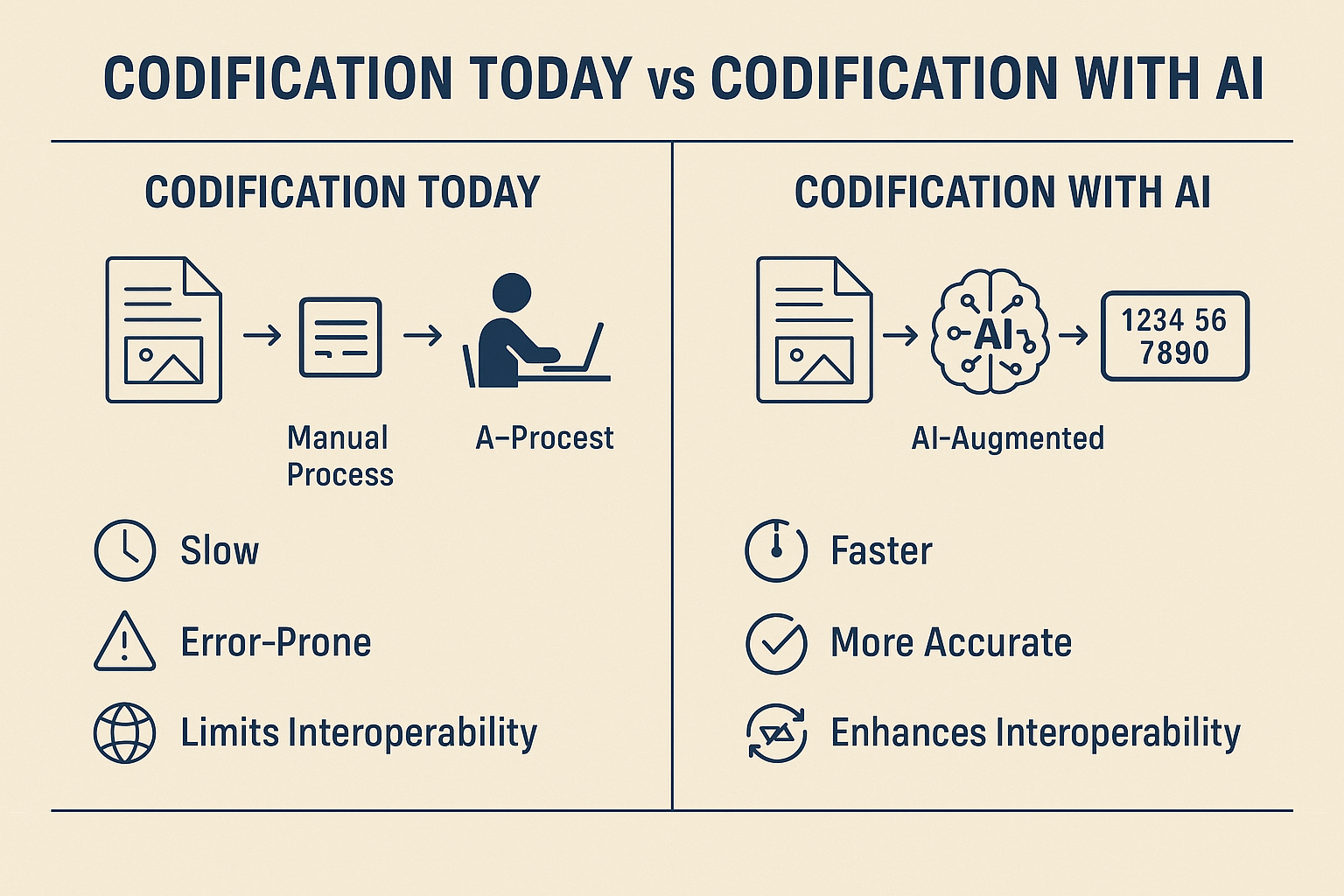

⚠️ Data Quality

Early failure data may be sparse or unreliable. Mitigation: Invest in digital twins and advanced analytics to improve predictive capabilities.

⚠️ Organisational Culture

Convincing stakeholders to trust a progressive approach can be hard, especially in high-consequence sectors like defence.

Five Key Lessons for Supply Chain Leaders

Resist the Temptation to Overbuy Buying everything up front may feel safe, but it often creates hidden risks. Invest in Data and Analytics Reliable data is critical to making dynamic sparing decisions. Build Flexible Supplier Relationships Partner with OEMs and service providers to share inventory risk. Communicate the Benefits Help stakeholders understand how phased provisioning supports readiness and sustainability. Plan for Adjustments Assume your initial sparing plan will change – and design processes to accommodate that.

Conclusion: From “Buy Big” to “Build Smart”

The next time your organisation introduces a new fleet, consider this: buying all the inventory up front might solve some immediate fears, but it can create longer-term headaches.

A phased, data-driven approach to inventory build-up offers a smarter, more sustainable alternative – one that aligns operational readiness with financial and environmental responsibility.

In today’s dynamic, contested supply chains, success belongs to those who can adapt, respond, and scale intelligently. The old model of “buy big and hope for the best” no longer cuts it.